March 2020, Boston, Massachusetts: The panic phase of the COVID-19 pandemic was at fever pitch in Boston and the sense of impending doom was pervasive. Shocking scenes from Wuhan and Italy filled the news feeds. Despite a paucity of concrete information on the novel coronavirus strain, none of the news was good. As a consultant in intensive care medicine and pulmonary disease at Boston University Medical Center, I read these reports with increasing dread as we started to see the first cases of COVID-19 pneumonia present to Boston hospitals.

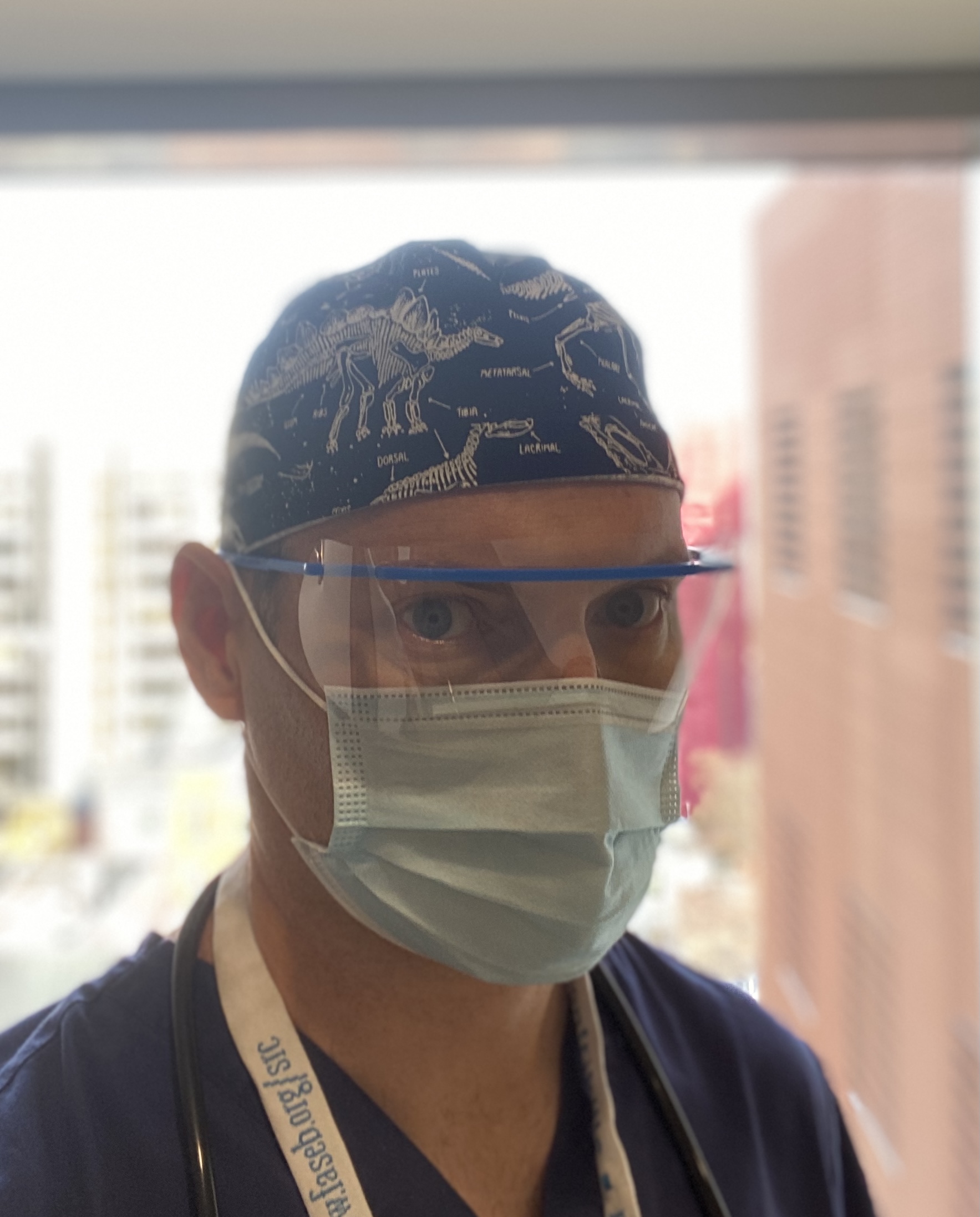

As physicians and scientists there was no way of knowing the precise interventions needed at that point to control the pandemic, but we knew for certain that national and international responses were severely lacking. It was not a matter of “if” but “when”. We were headed into a storm the likes of which we had never experienced but the questions were “when” and “how bad”? This “quiet before the storm” had all of the foreboding but was far from quiet. Spurred by the tsunami of cases that overwhelmed New York City hospitals, the city was in overdrive to prepare for the possible scenario of caring for hundreds, possibly thousands, of ventilator-dependent patients per day. COVID-19 cases started to fill the emergency departments and with heartbreaking predictability the ICUs. I barely slept the night before my first tour of duty in our COVID ICU. I wondered if this was what it felt like before being deployed in a war: fear of an invisible enemy, fear for your patients, your family, friends, colleagues and your own wellbeing. As dawn broke over the deserted streets of Boston I thought about the decisions that had led me to this point. Like many, my training kicked in and the scale of the task at hand mostly distracted from the fear.

December 2006, Galway: I was faced with the decision of staying in Ireland for medical training, or leaving. I grew up in Galway for the most part. In secondary school, Medicine seemed a far reach but my closest friend and I committed to getting the leaving cert points necessary. With family and friends in Galway I barely considered other Irish universities. Fortunately, I found that I loved studying Medicine. Learning about things that I found fascinating was much more appealing than the alternative. The medical training was excellent and we were held to a high standard. By the final year of medical studies when most of the focus is on clinical medicine, that is understanding, diagnosing and treating disease, I felt in my element. We had many excellent instructors and I was particularly impressed by some of the newly appointed consultants who had recently returned from the U.S. including Dr. Donal Reddan, Dr. Anto O’Regan, and Prof. Tim O’Brien who had taken over as Dean of Medicine in 2001. I graduated in Medicine from the National University of Ireland, Galway in 2004. I decided to stay in Galway for internship and house officer training. As this initial phase of training neared its conclusion, I had a strong inclination to further my training abroad, for at least a time. Prof. O’Brien and Dr. Reddan encouraged me to consider a new collaboration between University Hospital Galway and the prestigious Mayo Clinic. The program was designed to give Irish trainees an opportunity to experience US medical training and I would be the first envoy from Galway. In June 2007, having completed my US medical exams, I arrived in Minnesota and joined their internal residency program. For the next year, I rotated through a different medical specialty every four weeks meeting new residents, fellows and attendings every time.

December 2007, Rochester, Minnesota: At 4:30 am I showered, dressed, and left my apartment to start pre-rounding in the medical ICU of the Mayo Clinic. Had I come to appreciate the predictable nature of weather in the U.S. compared to Galway, I might have been spared the very unusual experience of having one’s hair and eyebrows freeze. It was -15 degrees Celsius. I defrosted as I reviewed the overnight events of the patients I was caring for. Like the ICUs in Ireland, we cared for critically ill patients but the difference here was the scale. Consistently ranked in the top 3 U.S hospitals, Mayo served patients from the local counties, neighboring states, and patients with complex and/or rare disease who travelled there from all over north America, Europe and Asia seeking care. As a result, the ICU was very busy and very demanding. It was the hardest I had ever worked but the high standards of care and the camaraderie made it a most rewarding clinical experience.

Friends wondered why I would put myself through an additional two years of essentially continuing as a house officer instead of progressing career-wise. At Mayo, the answer was obvious: it was a completely different and complementary experience. The sheer scale of the hospitals, the number of patients, the scope of diseases, and the expertise of the doctors was immense. For example, the Cardiology dept alone had well over 100 attending Cardiologists, many considered world experts in specific cardiac conditions. I was surrounded by physicians from all over the U.S., Central and South America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Australia. The strong foundational training paired with the intense working schedule, daily educational curriculum, focus on evidence-based medicine, access to state of the art testing, and exposure to hundreds of different specialists was an experience hard to replicate. It was amazing to see how physicians from very different places brought those experiences to the Mayo Clinic where the common goal was to practise medicine at the highest level.

The experience at Mayo compelled me to pursue a fellowship in the US. I completed a Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine fellowship at Boston University in 2013. This captured the two specialties I enjoyed the most; lung disease and intensive care. It was a very different experience to Mayo, serving as the largest safety-net hospital in the state and serving many patients from underrepresented minorities and vulnerable populations. During my training I joined a basic science laboratory exploring lung regeneration and led by Prof. Darrell Kotton. The research focused on a newly discovered type of stem cell, called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). For background, embryonic stem cell research was very much in the news at that time. Compelling because in theory those cells from human embryos could regenerate organs, but controversial due to the ethical and moral dilemmas associated with obtaining discarded embryos. iPSCs are virtually indistinguishable from embryonic stem cells but crucially can be made from a simple blood sample from any individual. The scientist who discovered these iPSCs was awarded the Nobel prize for Medicine a mere 6 year after their initial description.

From 2010 to 2017, I dedicated myself to deciphering the cues that would coax iPSCs into lung cells so that we could better understand human lungs and the disease that affect them. I am happy to report that we and others have now made significant progress in this endeavour and it is still remarkable to me to consider that blood cells can be reprogrammed in functional lung cells, or lung organoids, and are now being applied to studying a variety of human lung diseases. In 2018, I became the principal investigator of a research laboratory funded by the National Institutes of Health in the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University. Our research uses iPSC technology to generate functional airway cells from any individual and via this approach we study a number of lung diseases. Our hope is that this platform will lead to break throughs in understanding disease pathogenesis and in developing treatments for lung diseases. In addition to the research program, I direct the Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic at Boston University Medical Center where we care for patients with myriad forms of inflammatory and fibrotic lung diseases.

July 2021, Boston, Massachusetts: The last 16 months have taken their toll. At our peak during the surge, our hospital cared for over 200 hundred COVID in-patients with almost 60 in the ICU. Back-up after back-up teams were activated and despite the unprecedented numbers of critically ill patients, we were able to avoid being overwhelmed. Our Pulmonary Dept, composed of almost 30 ICU attendings and 20 fellows were scheduled around the clock. Despite these valiant efforts, I will always remember the many individuals who were not fortunate enough to survive and those who endured prolonged illness and face long term debility. With all the physicians scheduled for ICU duties, our research trainees were not satisfied to sit idly by. They worked tirelessly to develop and deploy testing strategies for COVID-19, performed and published studies to understand how SARS-CoV-2 initially infects the epithelial cells lining the lung, and shared these studies with any interested collaborator performing SARS-CoV-2 research. As life returns to a new normal, a rare positive is the invigorated understanding by many of the importance of basic science research.

I am very grateful that I trained in Galway and to those who made my initial adventure to the US possible. It opened doors that I did not realize were even there and exposed me to a broad swathe of medicine; some bad, some good and some outstanding. I try to take the best of those experiences for my own practice.

Profiles

Assistant Professor of Medicine/Principal Investigator/Director of the Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) clinic, Boston University