The value proposition of automation couldn’t be simpler: replacing human labour, mental or physical, makes things cheaper – and that is an economic force of gravity. But it also enables unimaginable plenty, perfection, reliability, and scale in the projects it touches. Automation also gives improvability: when we make improvements to automated processes, they stick and accumulate over time, whereas improvements in manual processes are often lost to forgetfulness or failure to transfer from one worker to another.

Of course, all sorts of large infrastructure such as transport and communications networks would be impossible without physical automation. So would the management of large businesses without information processing. The same is true in science. For example, in the Polifonia project, in which we are studying Irish traditional music, statistics of common snippets of musical material allow us to find relationships among tunes. The calculations could, in principle, be done on paper, but not in practice. Of course, we have to squeeze out the magic of live performance in order to analyse the material, but good results are still possible.

Something similar happens in the arts. Sticking with music: wax cylinders, player pianos, and eventually Spotify have mostly replaced live musicians as the most common way of listening to music. This has been a win for listeners because, for most, the alternative to recorded music is no music at all. When drum machines and sequencers became available, they automated certain aspects of performance and composition. Musicians and audiences quickly embraced the possibilities. Even human performance is now sometimes influenced by drum machines’ strange perfection.

So, as Shoshana Zuboff writes, “Whatever can be automated will be automated.”

For workers, automation has generally been good news. The Luddites, understandably, feared for their jobs, but until recently, every wave of automation has resulted in more jobs – usually better ones – replacing the obsolete. Millions of people have been spared from working jobs which are dangerous, or dirty, or just plain drudge. Even drummers haven’t gone out of business.

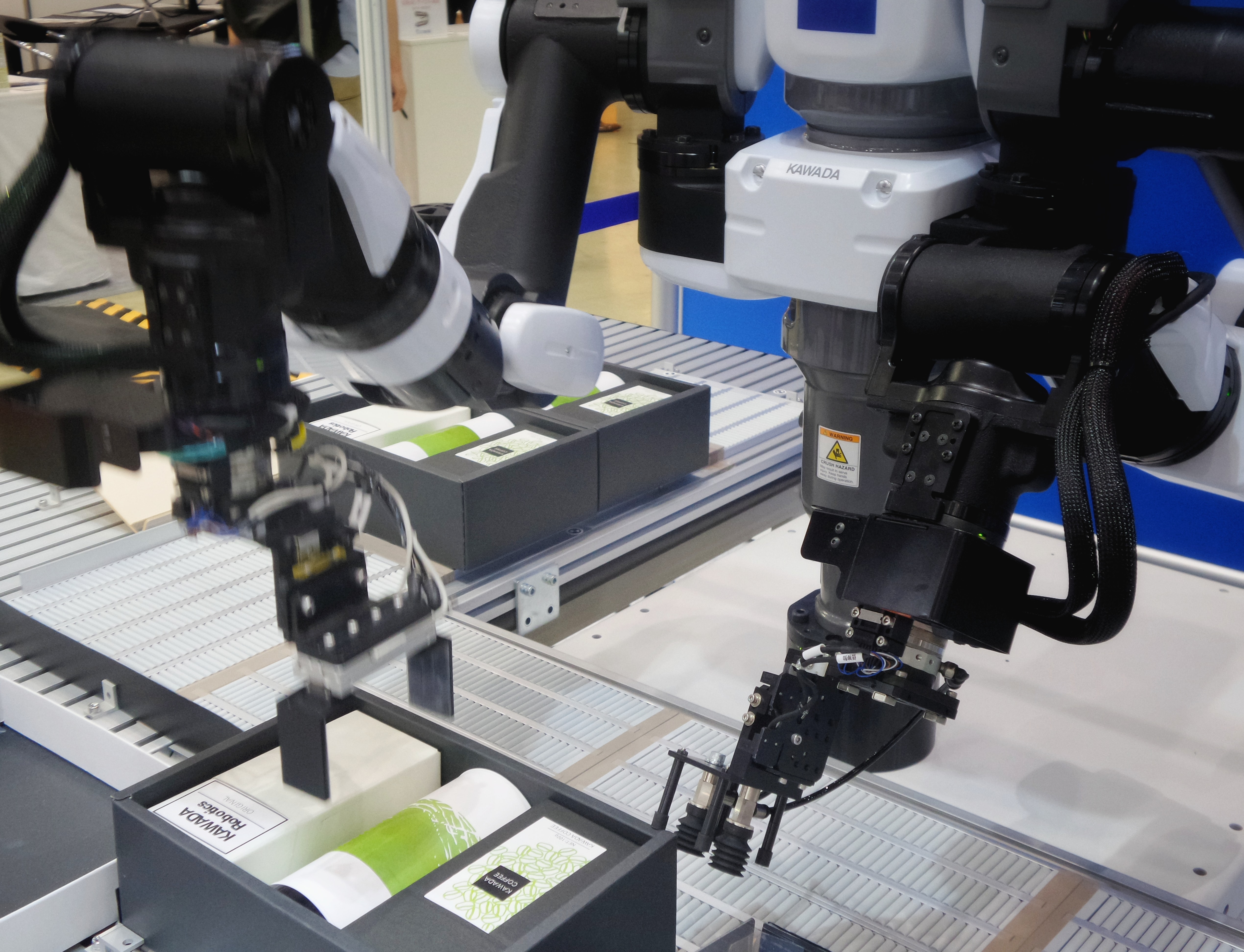

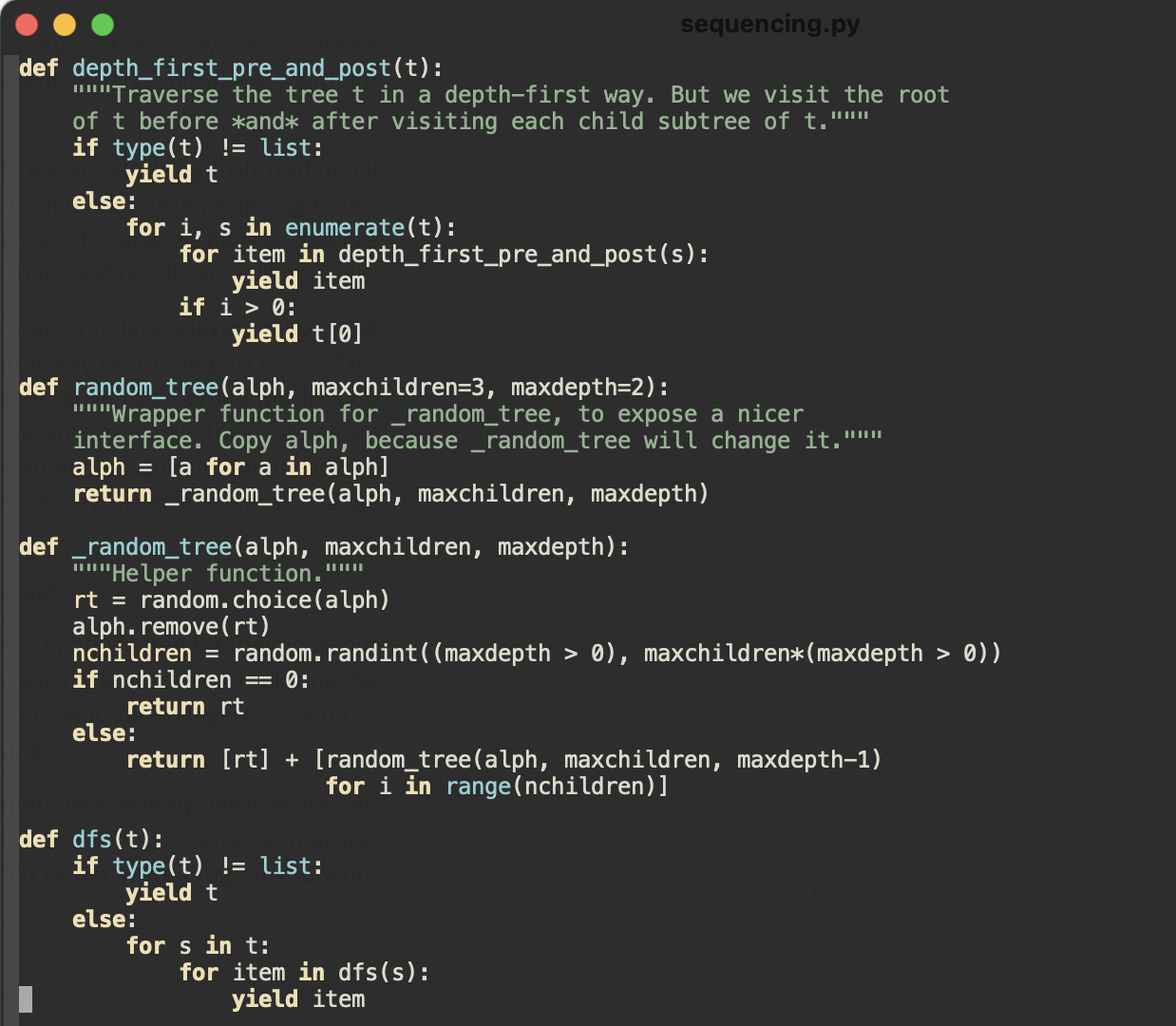

Some jobs that came into existence through automation – for example, repetitive assembly-line jobs in semi-automated factories – will likely go away again as computer vision and robotics systems improve. Another candidate is computer programming: Richard Sites said, “I’d rather write programs to write programs than write programs.” This is called metaprogramming or automatic programming. In the last few years, we have seen real progress by AI approaches (E.g. GitHub Copilot). This move up to a meta level is key, as we will see.

Automation versus labour

But Zuboff also rightly identifies a conflict of interests here. Automated processes don’t unionise or go on strike, and this is part of the appeal of automation – for capital. I said above that automation has generally resulted in the replacement of obsolete jobs with more jobs, and better, but this trend seems to have reversed in recent decades (1). It may be that as robots and computers get better, there is less room above them for us to do useful work. A Universal Basic Income is a possible solution to the resulting problems of unemployment and inequality.

But a different problem is our need for fulfilling and dignified work. Humans seem to have an instinct to enjoy skilled, concentrated work. We experience “flow” when we use our minds and bodies at a “just-right” level of challenge (2). People experience flow and fulfilment in activities such as knitting, woodworking, and computer programming.

Unfortunately, the economic force of gravity doesn’t favour fulfilling jobs per se. Quite the opposite: these jobs become uneconomical or over-subscribed, so for most people they are hobbies, not jobs. Musical performance was in this category long before automation. Computer programming might be safe from this trend for now, because a good programmer with good automation tools becomes an even more powerful programmer. But again, it’s not clear whether there is much more room at the top. Being a mere supervisor of skilled robots doesn’t seem likely to engender flow.

Automation as a creative act

Automation doesn’t just arise from a will to profit. Automation is itself a creative, enjoyable activity. It requires knowledge of the underlying task, and a deep sympathy for it. One way the urge to automate arises, I feel, is when the worker moves past a flow state. A task that was interesting or fulfilling becomes slightly more routine due to repetition and mastery.

My favourite example is generative art and music. As conceptual artist Sol Lewitt said, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art”. In generative music, a composer who is deeply engaged with their task and their material begins to see, either implicitly or explicitly, the rules and patterns that are governing their compositional process. Instead of continuing to write, they decide to make a system which embodies these rules. This is metacreation (3). It’s no longer spontaneous, so something’s lost, but something’s gained: a new understanding and new expression of their art. The artist becomes a witness to the music, as Brian Eno says, sometimes surprised by outcomes.

One of the beneficial outcomes is that new tools for automated accompaniment are democratising music – gatekeeping by cost and by the academy are reduced. But some employment opportunities for composers could disappear.

In my own case, I’ve used generative music as a way to write pieces that I could not have written otherwise. I wouldn’t have had the time and patience to write by hand all the details in my generated piece “Tomorrow is a new day”. But then, I wouldn’t have been able to write the code that generated those details if I hadn’t spent countless hours composing the old-fashioned way first.

The future of automation

What activities remain un-automatable? Of course, there are tasks that require human empathy, trust, accountability, or authority, for example aspects of healthcare and of government. There will always be a market for the hand-made, the artisanal, and the bespoke, as long as potential buyers are not themselves impoverished by automation.

Then there are tasks that require highly general and varied abilities, comparable to humans in ability and generality, and these are farther in the future. Mental tasks with this property are called “AI-complete”. For example, carrying on an extended, human-like conversation, as in the Turing test (4). We could coin a term such as “android-complete” for physical tasks with the same property. An example I like, perhaps a counter-intuitive one, is the work of a jobbing carpenter. A robot capable of the necessary range of dexterous action, use and choice of tools, flexible work in difficult spaces, use of multiple senses, and choices of action depending on experience and physical intuition – I think such a robot would be capable of working in many different areas also.

Estimated timelines for general AI vary, but have shortened recently, with median estimates probably in the 2030s–2080s. When this happens, we’ll see automated businesses, automated science – the sky is the limit. We won’t be able to ban automation but we have to protect human interests. We have a lot of thinking still to do.

(1) Acemoglu and Restrepo, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Work”, 2019

(2) Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi, “The Concept of Flow”, 2014

(3) Whitelaw, “Metacreation: Art and Artificial Life”, 2004

(4) Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, 1950

Profiles

James McDermott is a Lecturer in Computer Science in the National University of Ireland, Galway. He holds a BSc in Computer Science with Mathematics from the National University of Ireland, Galway, and a PhD in evolutionary computation and computer music from the University of Limerick. He has also worked on supercomputing in Compaq/Hewlett-Packard. His post-doctoral work was in evolutionary design and genetic programming in University College Dublin and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His research interests are in program synthesis, evolutionary computing, artificial intelligence, and computational music and design. He has chaired the EuroGP and EvoMUSART international conferences, is a member of the Genetic Programming and Evolvable Machines journal editorial board, and associate editor of ACM SIGEvolution.