Meadhbh McNutt: How do you define creativity?

Ikenna Anyabuike: For me, creativity is defined by any action which necessitates some type of subconscious, yet critical desire. Art can be beautiful and peaceful, but it can also be ugly, biting, scathing. Creativity is dictated by our ability to introspect and empathise with others.

I was talking with another artist, and she said to me, “We’re all so self-obsessed; we’re artists!” It’s true that there is a level of egocentrism, but creativity exists in this strange, liminal space of subconscious desires that grow and critique themselves, then grow and critique the world around them. It’s this constant critical reflection that manifests itself in art.

It’s important because isolation is often rewarded within our society—working from home, getting food delivered, Netflix. I think these are all good things in making content, food or work more accessible to those who may have physical or mental limitations, but the offset of that is a society where you can choose to, or accidentally, fall into a state of complete isolation. I like being alone for extended periods of time, but I think it can be dangerous to view human connection as an antiquated relic.

MM: Thinking beyond career success and the obvious benefits of creating and writing, what do these practices bring to your life that is unique, that keeps you coming back?

IA: When I am in the process of making art, it is the only time in my life where I feel a deep, never-ending connection. Apathy is like a drug. Once you engage in it, you don’t know how you found it but suddenly, you’re using it to cope. We live in such an uncertain world that so many young people, especially in minority groups, become extremely apathetic, myself included. The only way I can truly resist that is through the creation of art, at least in the short term. When I’m creating art, I feel—not even a sense of purpose, because I don’t think existence has to mean something—but a letting go of my hesitancy and a deep spiritual connection to whatever I’m creating.

MM: I noticed that you write about Eros [a concept in ancient Greek philosophy that refers to the erotic and in a wider sense, “life energy”], and tapping into that connection with life. As part of the Active* Consent programme, you’re currently on tour with the play, “The Kinds of Sex You Might Have at College”. Can you tell us about your role in the play and wider project?

IA: I am an ensemble member and “Deviser Assistant”. Our Artistic Director, Dr Charlotte McIvor is excellent at giving you a scene and making sure that it travels maybe five different hands before it comes back to you. My knee-jerk reaction to that was, “Ah!” because I wasn’t used to that kind of process, but it was very fruitful. The project gave me a real appreciation for collective consciousness and universal themes.

It’s been a privilege to be able to act in different environments and seeing people communicate how much they love the play. We were privileged enough to be given disclosure training by the Galway Rape Crisis Centre. Inevitably, due to the concept of the play, people disclose sexual assault to us. So, we are able to handle that and send them on to the correct facilities. We also got to do a Culture Night at the Galway Rape Crisis Centre amongst psychiatrists, survivors and people viewing the performance.

Consent literacy is critical for sex, but it’s not just about sex. Consent literacy is needed for every aspect of life. I love boxing and fighting sports, for example but if I find some random guy on the street and punch him, that’s really messed up. That’s assault, but if we shake hands, talk and agree to meet up in a boxing club to spar, then when one of us gets a little tired, we stop—that’s a lovely sparring session.

MM: Thinking beyond career success and the obvious benefits of creating and writing, what do these practices bring to your life that is unique, that keeps you coming back?

IA: When I am in the process of making art, it is the only time in my life where I feel a deep, never-ending connection. Apathy is like a drug. Once you engage in it, you don’t know how you found it but suddenly, you’re using it to cope. We live in such an uncertain world that so many young people, especially in minority groups, become extremely apathetic, myself included. The only way I can truly resist that is through the creation of art, at least in the short term. When I’m creating art, I feel—not even a sense of purpose, because I don’t think existence has to mean something—but a letting go of my hesitancy and a deep spiritual connection to whatever I’m creating.

MM: I noticed that you write about Eros [a concept in ancient Greek philosophy that refers to the erotic and in a wider sense, “life energy”], and tapping into that connection with life. As part of the Active* Consent programme, you’re currently on tour with the play, “The Kinds of Sex You Might Have at College”. Can you tell us about your role in the play and wider project?

IA: I am an ensemble member and “Deviser Assistant”. Our Artistic Director, Dr Charlotte McIvor is excellent at giving you a scene and making sure that it travels maybe five different hands before it comes back to you. My knee-jerk reaction to that was, “Ah!” because I wasn’t used to that kind of process, but it was very fruitful. The project gave me a real appreciation for collective consciousness and universal themes.

It’s been a privilege to be able to act in different environments and seeing people communicate how much they love the play. We were privileged enough to be given disclosure training by the Galway Rape Crisis Centre. Inevitably, due to the concept of the play, people disclose sexual assault to us. So, we are able to handle that and send them on to the correct facilities. We also got to do a Culture Night at the Galway Rape Crisis Centre amongst psychiatrists, survivors and people viewing the performance.

Consent literacy is critical for sex, but it’s not just about sex. Consent literacy is needed for every aspect of life. I love boxing and fighting sports, for example but if I find some random guy on the street and punch him, that’s really messed up. That’s assault, but if we shake hands, talk and agree to meet up in a boxing club to spar, then when one of us gets a little tired, we stop—that’s a lovely sparring session.

MM: That’s a good way of putting it. Do you see art as an impactful vehicle for social change?

IA: Absolutely. I’m a big fan of [American playwright, musician and novelist] Suzan-Lori Parks, as well as Augusto Boal, a Brazilian theatre-maker who designed the form of theatre called “Theatre of the Oppressed”. Boal would go to impoverished areas and communicate through plays how to strengthen interpersonal relationships, exploring things like mutual aid and spousal relationships to build healthier communities.

It’s really interesting because your mirror neurons are more engaged when you watch a play than when you watch a movie. They have actually scanned people’s brains after seeing a play, and they found that certain sections of your body, like your amygdala and sections of your dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) are more engaged. Your heart rate goes up. I think it’s because theatre exists in this psychological nexus where it’s not real, but the bodies are. If an actor was to fall six feet from the stage, that would be an actual human being falling. So, it has a more visceral effect on your nervous system, both as an actor and as a performer.

We underestimate just how much of our scripts and social cultures are dictated by the media—both for positive and negative reasons. I am huge fan of reading about black philosophy and civil rights, and the depiction of black people in media has played a large role in normative negative racial stereotypes. It’s only now that people are beginning to attempt to resolve that.

MM: That’s a good point. I was reading Audre Lorde recently on finding freedom through poetry. In poetry, you can trust that you have something to say, without the [validation] of rational thought in the stereotypical sense.

IA: Audre Lorde is fantastic. I recommend her essays, “Poetry is Not a Luxury” and “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”. Something that is beautiful about her work is the reverence she has for the beauty of creating without a construct that dictates what that creation is, and becoming more in touch with yourself. We do live in a capitalist society and have to make money, but doing so can allow us to become spiritually disconnected with ourselves because we are creating for an end goal, rather than an explorative one.

There is a great quote she has, “Revolution is not a one-time [event]”—and one is not free until everyone is. While that might seem utopian, we put a dog in a spacecraft and a human being on the moon with technology that was equivalent to half of that used in an iPhone today. We could probably fix a lot of other things.

MM: A reading of your full-length play, “Black Magnolia” featured in this year’s Dublin Theatre Festival. Can you take us through its beginnings?

IA: I was accepted into The Baptiste Programme, a script development initiative at Smock Alley Theatre, in my final year at university. I was introduced to people that I’m now blessed to call friends— poet Dagogo Hart, writer and scholar Nandi Jola and director and writer Esosa Ighodaro. I read a lot about Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist and political philosopher from Martinique, who also wrote plays, as well as London playwright Arinzé Kene’s “Misty”. All of this [research] amalgamated in a fruitful development time.

“Black Magnolia” is a strange little oul play with two main characters—Felix and Naji. Two 17-year-olds who have just finished their last exam at school and are trying to cope as they grow into adulthood. The trials and tribulations, and the existentialism that comes with all of that.

MM: You are now progressing to a postgraduate course at University of Galway in Creative Arts Management. What sparked your interest in this career path?

IA: Something that I noticed among well-respected artists is that they can be good at the creative side, and not so good at the business side. You would be shocked to know the amount of artists who don’t know how to do an invoice. I’m really interested in the financial aspects of art. There is a quote that I heard once, “Your budget is as much an aspect of the artistic creation as the script itself.”

MM: In the art world, we’re often adding value to each other through collaboration, and it can get confusing. We could probably do with more education around management.

IA: Management is often a thankless job. I’ll take a good stage manager over something like a cool smoke machine any day of the week! It’s underrated, just how critical it is to have someone to communicate back and forth, someone to say, “You’ve spent too much time on this.” One of the reasons I’m doing this course is to develop an element of professionalism. When people work with me, I would like for them to know that they’re in good hands.

MM: In your view, how can third-level education support students on their path to becoming professional artists?

IA: A lot of people come to university expecting that it will provide the opportunities, and it will to a certain extent. It will give you an infrastructure. I can confidently say that I learned a lot, especially with writing. I used university to experiment. For my arts management module, I was like, “I’m going to experiment with different forms of advertisements.” I’m just going to see what works. I would then come back and ask my lecturer for advice. It was a circular feedback loop. I would always be using my college work outside of college, which meant that it had to be good. I couldn’t be like, “Hey, this is what I can do” with something rushed and terrible.

University is a place where you can meet lots of interesting people and take risks. Once you get used to taking risks, you’ll get better at applications and then you’ll realise, “I’m getting everything that I want. This is weird.”

MM: What kind of projects can we look forward to in the future?

IA: “The Kinds of Sex you Might Have at College” is now doing a secondary school run, due to popular demand. Also, our music group, ARMCANDY has just released an EP called “First Blue”. I’m busy working on some cool stuff for next year. 2023 is going to be a very daring year. I can feel it.

Follow ARMCANDY on Spotify, or on Instagram at @arm_candy_music

Follow Active* Consent on Instagram and Twitter @ActiveConsent

Profiles

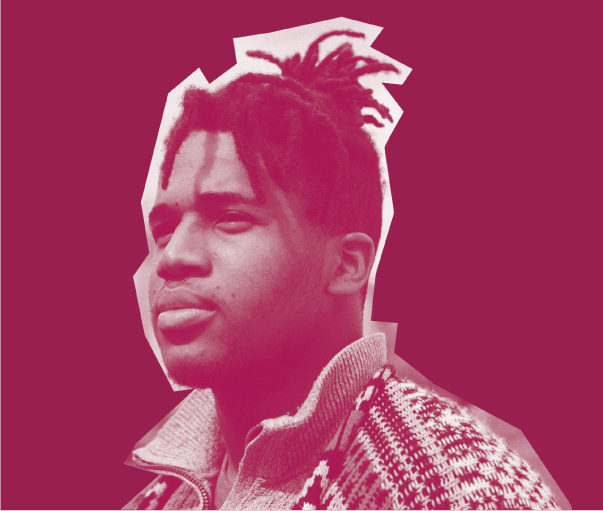

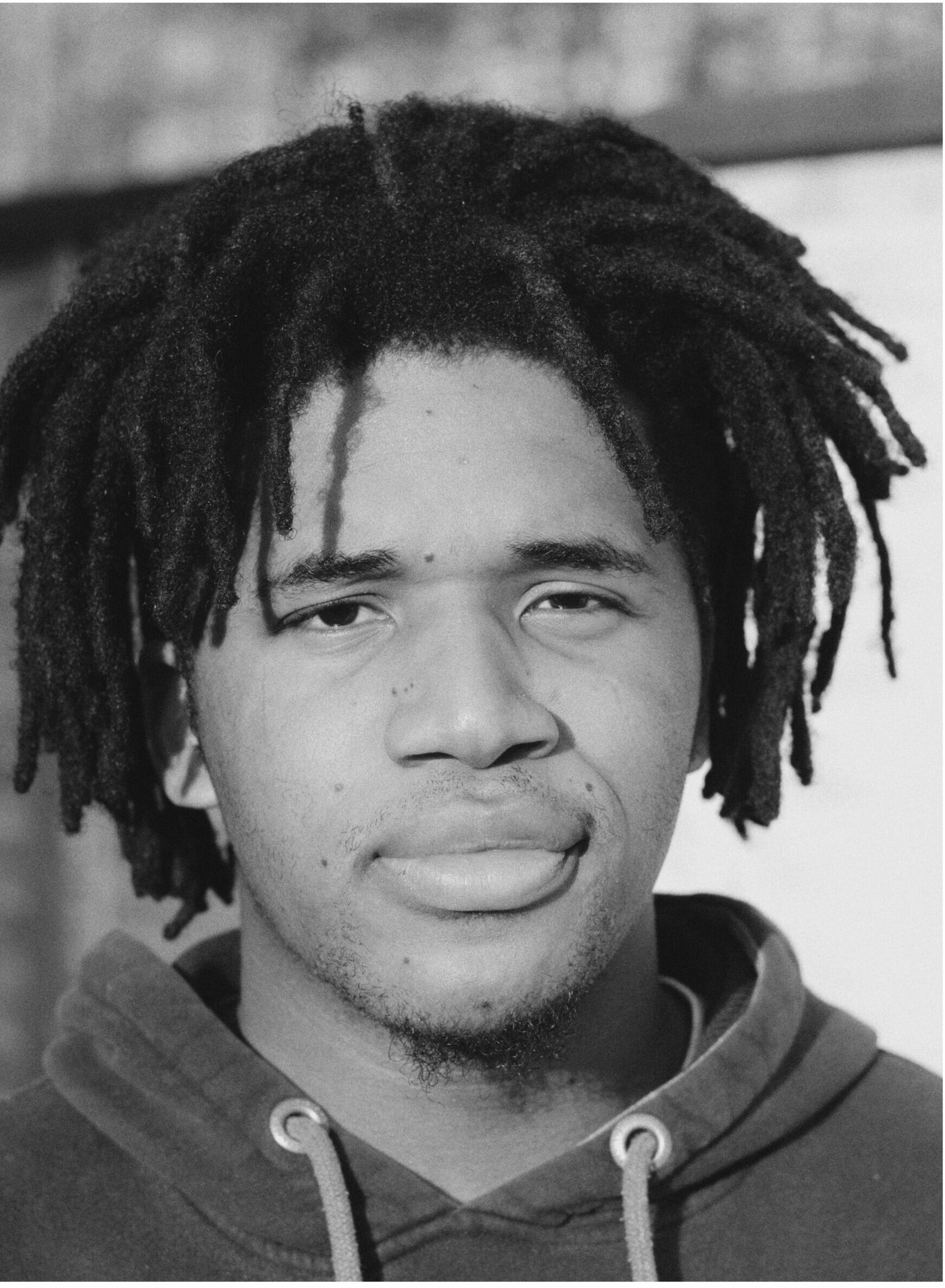

University of Galway student, Ikenna Anyabuike, is an actor, writer, assistant dramaturg and one half of the musical duo, ARMCANDY. Ikenna was awarded the ‘Baptiste Programme’ with Smock Alley in 2022, the ‘Axis Assemble 2022’ with Axis Ballymun and the ‘Irish Seed Grant’ by the Irish Hospice Foundation for an upcoming multi-media-based poetry exhibition ‘I Know The Sun Must Set’, in collaboration with visual artist Maclaine Black (scheduled for Q1 2023). He also performs as part of an ensemble for the play ‘The Kinds of Sex You Might Have in College’ with Active* Consent.

A graduate of Drama and Theatre Studies, Ikenna is continuing his studies in 2023 with a postgraduate programme in Creative Arts Management at University of Galway.