Individualism, homogenous algorithms, social cliques, unconscious biases—there are many challenges that we face in embedding empathy in society. Empathy and social values are widely recognised as the foundation of social cohesion and democracy. While there is evidence to suggest that empathy is on the decline, researchers at University of Galway are exploring ways to counter this trend. Empathy is best developed in an open and creative environment, where participants have agency over their own stories. Comparing research findings from across University of Galway, we can begin to piece together an understanding of the social conditions that allow empathy to flourish.

Can empathy be taught?

Dr Bernadine Brady was a Principal Investigator in the recent study at the UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre (UCFRC), assessing the attitudes and values of 700 12–16-year-old youths in Ireland on empathy, social values and civic behaviour. “In our quantitative research among 12–14-year-olds across Ireland, we found that empathy and civic behaviour was stronger among those who: (1) had opportunities to openly discuss social issues; (2) took part in youth work, drama and music; and (3) felt connected to community,” says Dr Brady. With support from the Irish Research Council, the study investigated key factors in the development of empathy among young people, noting a strong link between creativity and social cohesion.

Does social understanding always translate into action? Not necessarily. Another surprising observation from the UCFRC study is that, while many young people in Ireland demonstrate social understanding, they don’t have many opportunities to actualise that understanding through civic engagement. Creative engagement can act as a mechanism for equipping young people with the skills they need to thrive in a globally connected world. “At supra-national level, UNESCO and others have advocated strongly for global competencies,” says Brady, “the set of skills, values, and behaviours needed for young people to be prepared and thrive in a diverse, interconnected world.” (Pisa, 2018) Getting involved in a creative activity, whether that’s drama or music, offers an avenue for young people to bring their collective imagination to life and openly discuss their viewpoints. Put simply, young people are empowered as social actors in these settings, with the ability to “influence their own lives, the lives of others, as well as the societies in which they live.” (Lee et al, 2020)

Knowing this, how can we begin to integrate this kind of engagement into education? “We recognise that we, as academics, can play a role in creating space for dialogue and action around the concept of empathy,” adds Dr Brady. “To engage the public, we need to move beyond traditional modes of academic communication such as research reports and journals.”

The role of creativity and storytelling

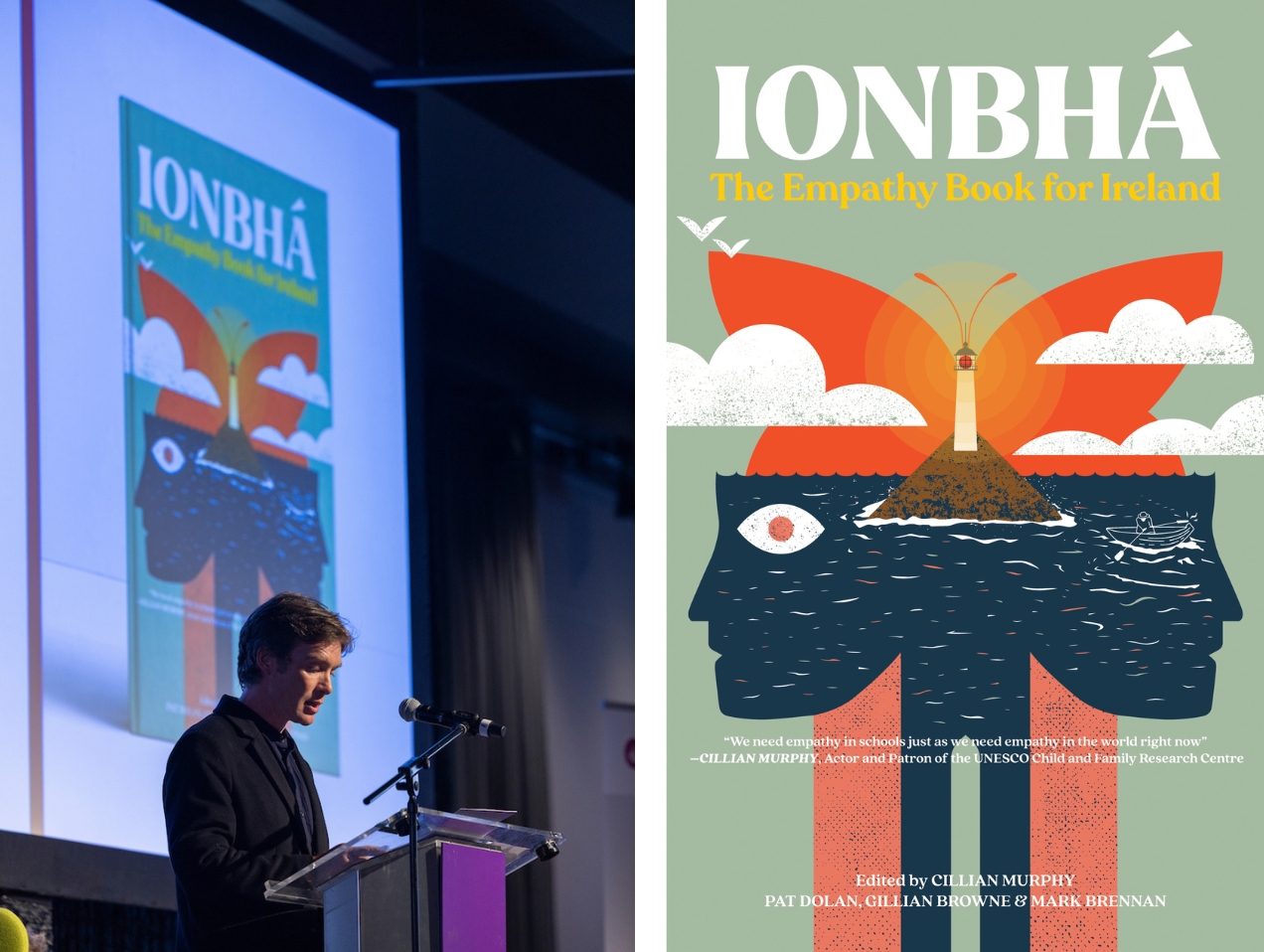

While most of us agree that acts of empathy are important, our experiences of empathy inevitably differ from person to person. Working with actor Cillian Murphy to advocate for change, the UCFRC recently published Ionbhá: The Empathy Book for Ireland with Mercier Press, a collection of reflections on empathy from people in sport, music, poetry and other walks of life. Now available to every secondary school in Ireland, the book empowers people of all ages to emulate these actions in a range of environments. Among the 89 contributors are Ireland’s President Michael D. Higgins, Hozier, Imelda May, The Edge, and Irish American Partnership Chief Executive, Mary Sugrue.

Ionbhá: The Empathy Book for Ireland is one of the many arenas in which the university is making a societal impact. Working with colleagues in the School of Education and Foróige, the UCFRC team is also co-producing experiential training programmes for secondary school and community settings. These programmes are designed to engage and support young people in embracing their role as active agents within their communities.

Storytelling, on whose terms?

We need storytelling to propel empathy; that much is clear, but who gets to tell their story and on what terms? These questions are significant following the advent of the internet. In the online sphere, storytelling is democratised, yet distributed on social platforms shaped by commercial interests and conditions. It can be tempting to throw digital solutions at problems of social atomisation. VR (virtual reality), with its pairing of storytelling and immersive technology, appears effective in combatting the individualism that we associate with a decline in empathy. The Immersive Empathy Project looks at both the possibilities and limits of VR as a tool for social change. Working with clients of Galway Simon who have experienced homelessness, the project aims to capture participants’ life stories as oral history and virtual reality.

“Since the emergence of so-called virtual reality 2.0 with the purchase of VR start-up, Oculus by Facebook in 2014, much has been written in academic literature and popular media about the power of VR to increase empathy levels towards marginalised communities,” says Film and Media Studies Lecturer and Immersive Empathy Principal Investigator, Dr Conn Holohan. “When we put on a virtual reality headset we are transported into another person’s environment and invited to walk in their shoes. However, as with any filmmaking practice, the wave of humanitarian VR films produced in recent years, have raised questions about who gets to tell their stories in these films and on whose terms, they are invited to speak,” says Holohan.

“Whilst viewers of virtual reality films can find themselves transported to a Syrian refugee camp or a slum in Kenya, critics of VR as a tool for social change have argued that they do so without ever leaving the comfort of home—that such films can act less as challenges to structural inequalities than as a form of misery tourism that ultimately leaves the viewer feeling good about themselves for feeling empathy towards those who are less fortunate.”

In facilitating a series of workshops, Holohan’s project empowers participants to tell their own stories through immersive film, exploring homelessness from the perspective of those who have lived it. He adds, “We are seeking to challenge the power relations of traditional documentary practice and allow the subjects of the film to shape the experience of the viewer.” The result isLost & Found, a fifteen-minute immersive film viewed through a VR headset. “The film has recently undergone a testing phase, wherein we track the impact of the film on viewers’ attitudes and empathy towards those who have experienced homelessness, in a controlled environment.”

The success of these workshops has opened up opportunities for the university to extend to the programme to transition-year students in DEIS schools, with support from Science Foundation Ireland. Using the methodology developed with Galway Simon, the next phase of Immersive Empathy workshops will combine STEM skills and creative practice, enabling students to explore storytelling and empathy as key tools for social transformation. The objective here is to offer a space to respond to social issues that are important to them, and to produce a creative and immersive experience.

What key insight can we take with us from the work of Dr Bernadine, Holohan and their colleagues at University of Galway? One point is startling clear: active empathy thrives in environments wherein agency, creativity and quality communication take priority. Creating such conditions is a long but rewarding process. “The goal of Immersive Empathy is to demonstrate the importance of transferring technical knowledge and creative control into those communities whose voices have been excluded from social debates,” says Holohan. “Its working premise is that only when communities are empowered to speak for themselves, to tell their own stories and challenge existing beliefs, can empathy between the viewer and the viewed provide a genuine platform for lasting social change.”

Discover Ionbhá: The Empathy Book for Ireland here.

Learn more about Immersive Empathyhere.

Profiles

Dr Bernadine Brady is a Lecturer at the School of Political Science & Sociology at University of Galway and a Senior Researcher with the UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre.

Bernadine is a mixed methods researcher with a focus on social ecology and young people’s wellbeing, exploring how community, school, family and service provision influence outcomes for young people.

She has published over 25 peer reviewed research papers in international journals, including Children & Youth Services Review, Children Society, Journal of Mixed Methods Research and Child & Family Social Work as well as a range of reports and book chapters. Bernadine has particular expertise in relation to youth mentoring, participation and evidence based practice in youth work.

Dr Conn Holohan is the Director of the Centre for Creative Technologies within the College of Arts, Social Sciences and Celtic Studies as well as a lecturer in the Huston School of Film & Digital Media at University of Galway. He has published widely on the ways in which cinema creates a sense of place, with a particular focus on the home, including a monograph and numerous journal articles and book chapters.

Conn is a researcher on the Immersive Empathy project, an interdisciplinary research project that explores the use of immersive technology to impact on empathy and attitudes towards socially marginalised groups.