In the advent of global climate change and ever-present population growth, food security is something at the top of people’s minds. To ensure that the populace is well fed, our agricultural practices need to align with demand. As the population grows, the demand for livestock productivity increases, which leads to higher, methane emissions which is a by-product of animals’ digestive processes. This means one issue cannot be addressed without tackling the other. In this Cois Coiribe article, Dr Sinéad Waters walks us through what potential and promising solutions look like for a more secure agri-food future.

Why Addressing Cattle Feed Is Crucial to Methane Management

The global population is currently 8.2 billion and is projected to reach 10.2 billion by 2100. With numbers this staggeringly high, it is estimated that we will need a 49% increase in global food production to feed the global population by 2050. Products such as dairy and beef, also referred to as ruminant products, are high in both protein and micronutrients and they are critically important in terms of food security, however global livestock production is contributing to approximately 18% of total anthropogenic – or human-influenced – greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Specifically, ruminant production which is a major source of methane, a GHG that has between 27 and 30 times the global warming potential (GWP) of carbon dioxide. This creates a difficult balancing act for the international agri-food sector, which must find ways to meet the rising food demand while also reducing their environmental impact.

The Environmental Footprint of Feed Digestion

Agriculture contributes ~37% of Irish GHG emissions, with methane accounting for ~70% of agri-emissions. Most of this methane comes from ruminant animals’ digestive processes, particularly from the fermentation of feed in livestock complex digestive tracts, (or four stomachs as it is sometimes referred to). Ireland has committed to reducing agricultural GHGs by 25% and was a signatory to the international Global Methane Pledge, which targets a 30% reduction in methane emissions by 2030. To meet this target, the agricultural sector needs to undergo significant change, and its impact will be felt across the whole of Ireland’s agriculture and food production system.

To address this issue, we must first understand the science behind it. Ruminant productivity and methane emissions mainly come from microbiological and biochemical processes. These processes occur within the rumen, a part of the digestive tract. It is the largest compartment of the forestomach in ruminants, such as cattle and sheep. Dietary carbohydrates are broken down by rumen microbes, and the rumen microbial community provides ruminants the unique ability to convert human indigestible plant matter into high-quality edible protein. Because of this, the rumen is an important aspect of animal biology, contributing to human food security. The process is, however, a double-edged sword, since this intricate microbiological process is accompanied by the production of the GHG methane gas, a by-product of digestion.

Rumen, Microbiomes, and Methane Mitigation

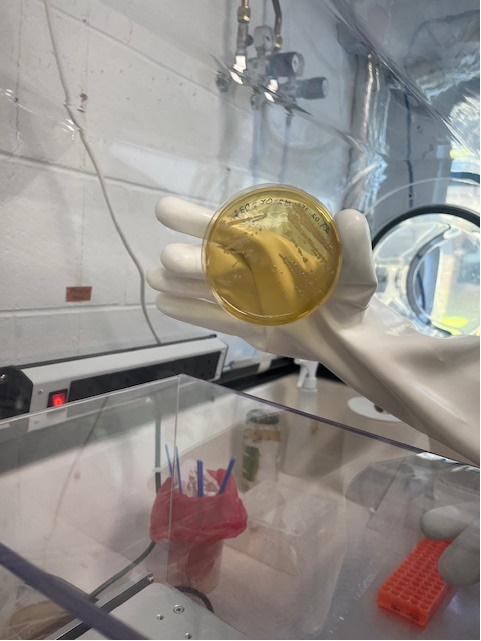

Our understanding of most microbiomes, including the rumen, is limited by their complexity and the lack of sufficient culture collections. It’s particularly challenging to culture anaerobic microbiomes, as there would be a need to mimic the very unique rumen environment in order to culture the constituent microbes. At the University of Galway’s Ryan Institute, we are working in partnership with the Global Research Alliance Flagship: RUMEN Gateway, to better understand the identity and functionality of the rumen microbiome. Our research focuses on the study of its diversity, ontogeny, and function using state-of-the-art anaerobic culturing facilities and microbiome sequencing technologies.

In recent years, our ability to culture rumen microbes has improved, largely thanks to the development of new culture media. This includes better rumen simulation, and use of innovative technologies like microencapsulation. A focus on culture – termed culturomics – combined with genome sequencing is returning, and these culture collections are hugely valuable to our fundamental understanding of microbiomes. Not only do they help demystify use of feed additives, probiotics and direct fed microbials (DFMs) and establish their modes of action, but they are also a source of bioactive compounds for biotechnological applications. Data collected from this research contributes to a global effort to expand our knowledge of the rumen microbiome, adding to microbial reference databases to support sequencing analysis.

We collaborate with key stakeholders – such as Teagasc, Irish Cattle Breeding Federation, DAFM, EU, and industry partners – on the development, validation and implementation of novel methane mitigation strategies using fundamental information on the rumen microbiome. These interventions, which include microbiome-assisted breeding values, feed additives, and novel direct-fed microbials (DFMs), could potentially benefit not only Ireland, but agricultural practices across the globe.

Feed Additives: A Gut-Friendly Solution

Collaborative research between the University, Teagasc, and industry partners has helped us progress the development and evaluation of nutritionally based solutions to reduce methane emissions in the agriculture sector. Through the DAFM-funded project Meth-Abate, we have evaluated a wide range of feed supplements and additives in sheep and cattle diets. These include Bovaer (3-NOP), novel rumen oxidising agents, seaweeds and their extracts, and fats, such as linseed and rapeseed oil supplements.

The data from Meth-Abate showed that using the internationally recognised Bovaer (3-NOP) in ruminant diets is a promising strategy to reduce methane emissions. In Ireland, we investigated the effects of adding 3-NOP to the diet of beef cattle. The results showed that 3-NOP reduced methane emissions resulting from these cattle’s digestion processes by 30% with no negative effect on animal health. A novel oxidising agent, which can be delivered in a pellet format – a major advantage for its on-farm delivery – was capable of rendering a 28% reduction in methane emissions. Supplementing cattle diets with rapeseed and linseed oils reduced methane emissions by 9% and 18% respectively. These results are substantial and show that methane emissions can be reduced if deployed on farms.

In Ireland, where ruminant production is mainly a pasture-based system, it’s crucial that the technology developed is designed to reduce agricultural methane emissions works when used in grazing systems. A major focus of our programme is to develop slow-release and bolus technology for the delivery of feed additives. Through the DAFM-funded project Methane Abatement in Grazing Systems (MAGS), we are working on new formulations, including slow-release and bolus technology, which will be developed and tested for pasture-based production systems.

Genetics and Other Science-Powered Considerations

Genetic improvement is cumulative, and a cost-effective technology. Selecting animals that produce lower methane has been advocated as a promising methane mitigation strategy. A successful collaboration between Teagasc and the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation (ICBF) showed that some beef cattle can emit up to 30% less methane while maintaining the same level of agri-food performance in food production.

Following these findings, the ICBF published the first international enteric methane across-breed genetic evaluations on different breeds, focusing on AI sires. This highlighted the importance of selecting cattle with low-methane emissions.

Our project is integrating microbiome data from thousands of animals to help develop new or novel microbiome-assisted genomic breeding values for methane emissions. Testing across different diets, will help improve the accuracy of selecting animals with lower methane emission. Ultimately, this data will contribute to a global initiative through the EU horizon project, HoloRuminant, which aims to develop and validate international microbiome assisted-breeding programmes.

As our population grows, it’s crucial to consider the implications for agricultural practices, not only on food production but also on the environment. By addressing these questions now, we can create a more sustainable and efficient productive agri-food future for our society.