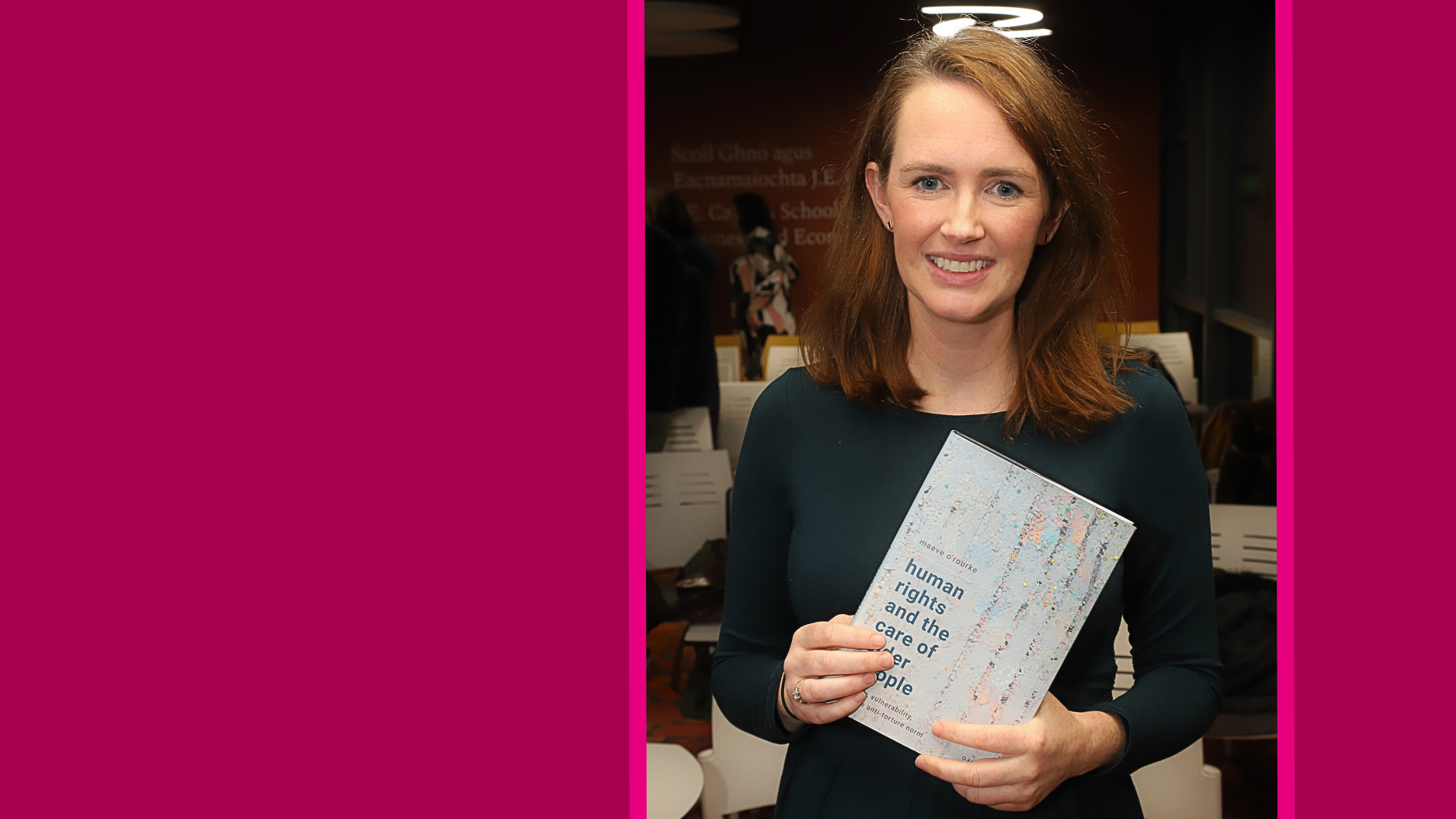

First published in the Irish Centre for Human Rights Blog, this article featuring Dr Maeve O’Rourke covers key arguments from her recently published book, Human Rights and the Care of Older People: Dignity, Vulnerability, and the Anti-Torture Norm (Oxford University Press 2024). Dr O’Rourke’s monograph explores international anti-torture norm in the conceptualisation of older people’s human rights. As described by Felice Gaer, former Vice-Chairperson of the UN Committee Against Torture in Geneva and pioneering international lawyer, it presents ‘a new and important assessment of standards for consent and care.’

Cois Coiribe is delighted to have the opportunity to spotlight this great achievement and provide insight into this topic which delves into core societal issues.

Care is a universal human need; we each experience it throughout our life in myriad ways. Whether and how we are responded to is a matter of how we are situated. This includes how state structures, and the societal cultures they create and stem from, operate in relation to us.

Around the world, people routinely face coercion and/or neglect in response to their care needs as they age. United Nations (UN) bodies among others consistently report older people’s widespread denial of legal capacity, restraint, forced medical treatment, forced institutionalisation (including due to lack of long-term home- and community-based services), subjection to physical violence and other degrading practices, and lack of access to care for chronic conditions and end-of-life care and palliative medication. It is perhaps the pervasiveness of older people’s care-related mistreatment that explains many states’ reluctance, according to the UN Independent Expert on Older Persons’ Human Rights, to acknowledge and set about taking the macroeconomic and administrative steps necessary to combat it.

In Human Rights and the Care of Older People: Dignity, Vulnerability, and the Anti-Torture Norm, I argue that the rule against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in international human rights law (and, by extension, in domestic legal systems) should be put to greater use in protecting older people from care-related mistreatment.

In principle my arguments apply to all of our need for care because they draw on states’ universal obligations under the anti-torture norm. However, the book’s analysis is prompted by and refers specifically to extensive health and social care-related literature concerning neglect and coercion of people deemed ‘old’ or ‘older’ according to various chronological age thresholds in regional or disciplinary practice. In addressing the care-related mistreatment of people considered ‘older’, the book proposes a method of legal reasoning under the anti-torture norm which can tackle discriminatory influences on whether and how care is provided to people—and which can justify mobilising and progressively interpreting states’ positive obligations to achieve dignified care in practice.

The book takes a global view, analysing key anti-torture doctrine espoused by African, European, Inter-American, and UN human rights treaty bodies, as well as the positions of many countries’ National Preventive Mechanisms (NPMs) created pursuant to the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture, and UN special procedures. My aim is for the book to be widely accessible so that it may be of practical use, and for this reason I am extremely grateful that it has been published Open Access through the financial support of University of Galway and the National University of Ireland.

The book begins by explaining the usual context-sensitive and individualised approach of the international human rights treaty bodies to determining whether prohibited ill-treatment is occurring such that states’ duties to cease or prevent such behaviour are triggered. For readers unfamiliar with the anti-torture normative framework, I highlight for example that feelings of humiliation and debasement are frequently central to a finding of ‘degrading’ treatment, and that intent to harm a person is not necessary for ‘degrading’ treatment to occur. My overview of existing jurisprudence illustrates the expanse of states’ recognised positive obligations to prevent and protect from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. These obligations include the creation of legislative and regulatory frameworks to address known risks of ill-treatment, proactive steps to facilitate access to justice—including measures to counteract societal marginalisation and stigmatisation, and the provision of socio-economic resources to protect human dignity where people are in certain situations of ‘vulnerability’ (the classic instance of which is deprivation of liberty).

From the above sketch, it may seem that the existing doctrine under the international anti-torture norm holds significant promise as a framework through which to understand older people’s care-related mistreatment, and as a vehicle for achieving concrete changes in their conditions. Indeed, my book argues that better protection of older people’s human rights is in part a matter of piercing through paternalism and prejudicial stereotypes to recognise the established doctrine’s relevance to older people’s lives. However, I also contend that certain ‘doctrinal dichotomies’ require dismantling in pursuit of the anti-torture norm’s principled, i.e. dignity-focused, progressive application to care-related mistreatment.

As a lens to assist human rights actors—be they older people, advocates, judicial decision-makers, dedicated human rights institutions or state officials—to interpret and apply the anti-torture norm more effectively, I offer a conception of a dignity violation sufficient to breach the rule against torture and ill-treatment in principle (i.e. assuming the minimum threshold of severity of suffering is met).

My conception of such a dignity violation is an interference with a core aspect of the personality, which the person is situationally powerless to avoid. It draws on, and draws out sometimes latent elements of, European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) jurisprudence, which I illuminate by reference to the work of numerous legal-philosophical theorists. My use of dignity as an interpretive lens relies on international treaty bodies’ and national courts’ long-standing resort to the concept to justify expanding the anti-torture norm’s jurisprudential application.

In a chapter on poor continence care, I use my conception of a dignity violation to explore the human impact of coercive and neglectful ‘care’ practices that older people commonly suffer—which are frequently prescribed or accepted as professionally appropriate. Focusing on the personality brings to light individuals’ reduction to pleading, crying and otherwise begging for help to keep clean or to use the toilet; their physical and psychological degradation through the acquisition of sores, infections and lasting incontinence; and their loss of control over their sense of self and others’ relation to them arising from how they are forced to present to the world. The parallels with prison conditions case law, in which treaty bodies and courts have recognised ‘degrading’ treatment to arise from the effects of inadequate sanitary conditions on the personality, become clear. The question then arises as a matter of anti-torture doctrine, whether older people in care settings or in need of care can be said to experience ‘vulnerability’ (analogously to those who are incarcerated) such that states must act to prevent their suffering due to inadequate care.

My conception of a dignity violation incorporates the notion of situational powerlessness, which I equate with vulnerability as I argue treaty bodies have done, albeit sometimes implicitly. Examining health and social care literature on poor continence care, I identify a range of sources of older people’s situational powerlessness to avoid the interference with core aspects of the personality that inadequate continence care frequently involves. These sources include the unavailability of consensual care services and supports, paternalistic culture and an accompanying denial of communication avenues or support that would insist on the person’s views and preferences being acknowledged, the related inaccessibility of complaints and other accountability mechanisms, institutional priorities that are not concerned with the individual in need of care, and economic policymaking and modes of resourcing that do not have the human rights of those giving or receiving care at their centre. States’ positive obligations under the anti-torture norm, I argue, must be applied in response to and with the aim of combatting these structural contributors to older people’s care-related mistreatment.

A further chapter focuses on older people’s widespread deprivation of liberty for ‘care’ purposes. Here, once again, I use the concept of dignity as a lens through which to appreciate the human impact of, and structural contributors to, coercion and neglect in response to basic needs. I highlight a range of effects on the personality of locked doors, un-navigable environments, requirements to relinquish financial and other means of travelling or living elsewhere, methods of restraint, social isolation, and institutionalising regimes on older people—as documented in health and social care literature. These effects include the denial of choice over how one lives; infringement of the person’s sense of place within community and family; loneliness, stress, anxiety and depression; deprivation of exercise and opportunities to maintain health through denial of access to medical care and allied health services; and the drastic alteration of consciousness and one’s ability to interact with the world through chemical sedation, where it occurs. The situational powerlessness which permits or constitutes the deprivation of liberty arises from—among other things—older people’s lack of access to person-centred, consensual care; subjection to substituted decision-making practices both formal and informal; lack of access to decision-making assistance and complaints and other accountability mechanisms; lack of state regulation including the involvement of for-profit commercial actors in providing institutional ‘care’; the nature (and absence) of training and professional development of staff; and the devaluing and exploitation of both formal and informal carers. States’ positive obligations under the anti-torture norm, I maintain, must be interpreted to respond to these structural sources of disempowerment and thus to prevent ill-treatment that contravenes the norm.

My analysis of the above problems leads me to argue that states’ positive obligations under the anti-torture norm, to prevent and protect from ill-treatment, should be interpreted to include a duty to ensure access to consensual care. This duty should be understood to require states to guarantee universal access to decision-making and self-advocacy support in relation to care, and to provide person-centred, consensual care services and/or supports where people depend on the statefor assistance to meet their basic needs.

I recognise as key elements of the anti-torture norm (i) states’ obligation to provide and organise socio-economic resources to protect dignity, and (ii) the universal right to respect for one’s legal capacity. Thus, my position challenges several doctrinal constraints (which I term ‘doctrinal dichotomies’) in the established international anti-torture legal framework concerning state responsibility for resource provision and the (im)permissibility of non-consensual medical intervention. These are areas where some human rights treaty bodies and soft law instruments historically have carved out exceptions to the ordinary rules under the anti-torture norm: I challenge the logic of these exceptions and argue that they contravene the fundamental purpose of the norm.

The ECtHR has long demonstrated reluctance to impose responsibility on states to provide socio-economic resources to alleviate suffering from lack of them, per se. The Court’s judgments under the anti-torture norm tend to tie state responsibility for resource provision to another form of responsibility for a person’s circumstances—eg arising from deprivation of liberty, the threat of deportation, or an existing domestic legislative requirement to provide care. The ECtHR cleaves to the notion, repeated frequently since Pretty v United Kingdom, that there is a realm of ‘suffering which flows from naturally occurring illness, physical or mental’ which sits outside the anti-torture norm’s remit because it is not and does not risk being ‘exacerbated by treatment, whether flowing from conditions of detention, expulsion or other measures, for which the authorities can be held responsible’. The idea that individuals are sometimes, and particularly when they are suffering ill-health, naturally unaffected by the behaviour of states or of those around them (to whose actions or inaction the state could respond) is challenged by the IACtHR’s approach to analysing the dynamics of health-related suffering under Article 5 of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), as I explore in the book. The idea is also undermined by health and social care literature showing that lack of access to care for basic needs inevitably renders a person powerless over how they relate to themselves and others because basic needs are unrelenting and therefore inescapable.

The UN Independent Expert on the human rights of older persons echoes wide-ranging research in stating that ‘coerced institutionalization is likely to happen where there are no other forms of care available, including a lack of home and/or community-based services, or when relatives are unable or unwilling to provide care and support’. Lack of access to resources to meet basic needs—and lack of legal recognition of state responsibility to provide such resources—therefore constitutes coercion, while also inviting further coercion by others (including state support for privately operated coercive systems) as the person’s powerlessness to respond to an unrelenting basic need is deemed to display ‘self-neglect’ and inherent ‘incapability’.

In the book I highlight the ECtHR’s 2014 decision in KC v Poland, concerning a 71-year-old woman’s detention by court order in a nursing home. Under Article 5 ECHR (the right to liberty), the Court found KC’s deprivation of liberty justified on the ground of ‘unsoundness of mind’—despite her treating doctors’ advice that although they had diagnosed KC with a ‘mental disorder’ there was no need for her hospitalisation and she did not pose a ‘direct threat’ to her own or others’ life or health. What KC did need, according to the state’s social services authority and assessing psychiatrists, was ongoing assistance with the tasks of daily living including hygiene and nutrition. Full-time home care was not available from the state authorities nor from her daughter. This led the ECtHR to find that KC ‘had neglected herself and her apartment and failed to observe the basic principles of hygiene and nutrition’ and therefore ‘the domestic court’s decision to confine the applicant in a social care home was properly justified by the severity of the disorder’. This unrestrained approach to determining the nature and so-called ‘necessity’ of mental health detention—the Court’s assent to describing KC’s lack of resources as ‘self-neglect’ and personal deficiency, justifying her detention—illustrates the very real influence that the state and others may exert over individuals’ experience of ‘naturally occurring’ illness and human need.

Relatedly, in my chapter on poor continence care I discuss the seemingly commonplace phenomenon of individuals’ lack of access to care for toileting needs leading carers to view the person as inherently incapable of maintaining continence and/or cleanliness. Reflecting this, in its 2015 judgment in McDonald v United Kingdom, the ECtHR accepted as professional practice the routine classification of older people who need mobility assistance to reach the toilet as ‘functionally incontinent’: in that case justifying a care plan by the state authorities that withdrew HM’s personal assistance and replaced it with incontinence pads and plastic sheeting. In the 2002 ECtHR case of HM v Switzerland, meanwhile, the Swiss state explicitly relied on the archaic and prejudicial concept of ‘vagrancy’—ie the notion that HM lacked a socially useful purpose—to justify an older woman’s court-ordered detention in a nursing home for physical care purposes. (The ECtHR did not adjudicate this contention because it refused to accept a deprivation of liberty had occurred in the first place.) These examples illustrate that lack of recognition of our universal right to assistance where necessary to meet our basic needs leaves a chasm in human rights law’s protection of human dignity. The chasm is filled and perpetuated by discriminatory notions of individual culpability, deficiency and disentitlement to freedom, masking state and societal mistreatment.

Crucially the entitlement to resources where a person is dependent on the state, which I argue should be recognised under the anti-torture norm, must be to assistance that does not disempower but rather empowers the person in respect of their personality—in accordance with dignity’s fundamental demand. My argument therefore challenges a second ‘doctrinal dichotomy’ in the international anti-torture normative framework, concerning non-consensual medical intervention. The book offers a way of interpreting the anti-torture norm compatibly with Article 12 UNCRPD (and Articles 14 and 19 UNCRPD) using a dignity/vulnerability lens. Such harmonisation, through the anti-torture norm’s principled progressive interpretation, is essential to the effectiveness not only of the anti-torture norm but of all related rights in international human rights law given the anti-torture norm’s relative strength, implementation infrastructure, and role as a backstop to social policy.

Article 12 UNCRPD mandates universal respect for legal capacity and obliges states to ‘provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity’, along with other safeguards to ensure universal respect for legal capacity ‘in all aspects of life’. The IACtHR has interpreted the ACHR to require the same. Yet, other human rights treaty bodies—including the ECtHR, UN Human Rights Committee, UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, and European Committee for the Prevention of Torture—persist in their adherence to the traditional bifurcated doctrine of ‘medical necessity’ under the anti-torture norm (and the right to liberty). According to this approach, on the one hand, informed consent to medical treatment is the sine qua non of dignity-respecting care, and non-consensual intervention may occur only in strictly emergency circumstances; on the other hand, a medical professional may deem a person ‘incapable’ of consenting and proceed to treat them in the way that the professional considers best. Their designation as ‘incapable’ deprives the person of the right to whatever assistance may be necessary to have their will and preferences acted upon.

An extensive human rights and health and social care-related literature evidences the methods by which states can meet their obligations under Article 12 UNCRPD, notably including the substantive provision and organisation of care and personal support options that respond to individuals’ will and preferences, as well as wide-ranging communication approaches. Drawing on this literature and Article 12 UNCRPD, I argue that denial of capacity is actually a denial of care. By engendering powerlessness regarding core aspects of the personality it violates the anti-torture norm in principle, I contend. What is more, attachment to the possibility of authorised coercion based on ‘incapacity’ precludes human rights actors from responding fully to the need for empowerment of all older people (and others) in relation to care.

Following the onset of the Covid pandemic, NPMs and human rights treaty bodies increasingly have recognised older people’s widespread deprivation of liberty for ‘care’ purposes. I argue that, in addition to uniformly denouncing deprivation of liberty for ‘care’, these and other human rights actors need to put intense interpretive effort into extrapolating from the anti-torture norm the substance of consent and empowerment in relation to care and the mechanisms of guaranteeing consent and empowerment in practice.

My hope is that this book acts as a catalyst for vigorous consideration of how one of the strongest international human rights norms can be harnessed to encourage the structural transformation that older people’s care policy and provision so clearly need to undergo in countries around the world. The benefit of a human rights law analysis for all those participating in older people’s care is that it places a primordial focus on the human experience of harm with the purpose of demanding that the state responds to such harm and creates structures to prevent it in the future. A human rights approach to care is therefore a collective endeavour in which we imagine and take steps to create the state apparatus upon which we all depend. More immediately, I hope that the arguments in this book will assist individuals and collectives who seek accountability for their mistreatment, whose articulation of their experience and its meaning in legal terms contributes vitally to human rights law’s functioning as a tool of societal reform.

Profiles