The imminent death of the social imaginary is the biggest challenge facing humanity. This is the diagnosis offered by Geoff Mulgan in his recent book, Another World is Possible: How to Reignite Social and Political Imagination (2022). At stake is society’s collective ability to imagine alternative ways of being, and the problem is that the connective spaces where such work can happen are falling away. Universities with a consciously creative, radically cross-disciplinary curriculum are a major part of his solution.

Mulgan is first and foremost a national policy advisor who has meanwhile found his way into UK academia. I am first and foremost an academic who is finding my way into government policy. We both care deeply about the socially transformative power of knowledge, but our starting points are very different. What might we have to say to one another if we were to meet on the design team for a radically creative university on the edge of Europe?

While Mulgan would bring his many years of experience in leading national initiatives to tackle social inequalities, I would bring with me a life of reading literature to draw out textual power structures. In particular, I would bring along the maverick Argentinian author, Jorge Luis Borges. Borges has made an art form out of enigmatic short stories that hinge on imagining the impossible, often by virtue of existing in multiple dimensions, or otherwise subverting conventional notions of space and time. Every batch of paperwork for university committees should include one of his pieces.

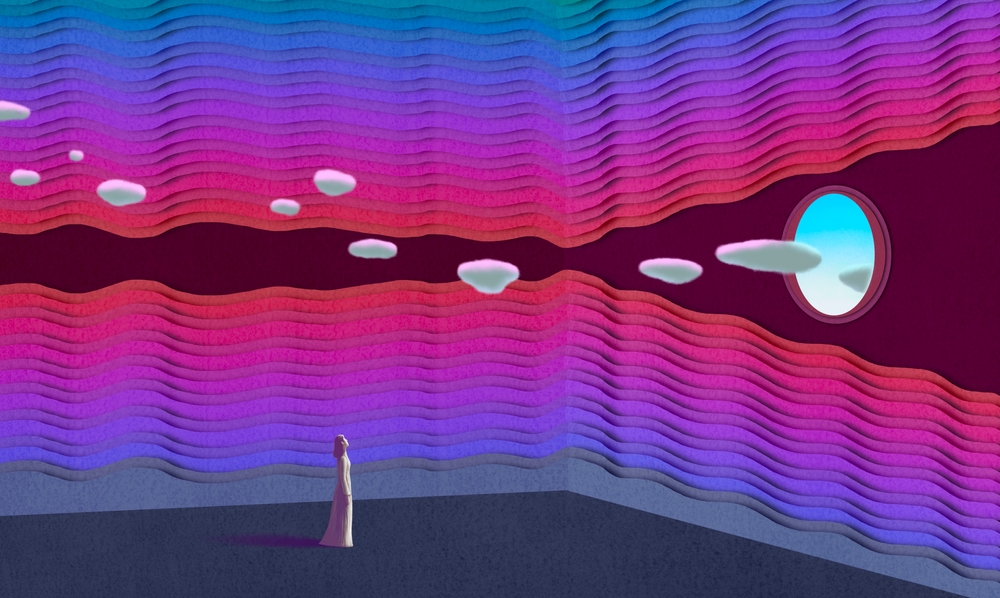

I am being only apparently flippant. The ability to imagine alternative ways of being and doing runs right through all disciplines in a university, and that sense of almost limitless potential is what makes a university such an inherently exciting place. In practice, however, there is also a tendency for the focus of knowledge creation and application across campus to become ever more indexical: honing specificity within a category, rather than standing back and linking up the insights. We are not as naturally good at communicating the greater value of our work as our pedagogical credentials imply we should be. This frustrates me greatly.The Creative University on the Edge of Europe designed by my imaginary team tackles this weakness head on. If Mulgan’s social imaginary is to come back from the brink of extinction and thrive, it requires a place within society expressly set up not just to facilitate but to actively demand big-picture thinking at every level of its operation. The social imaginary is not a theory that can be taught nor is it a method that can be applied. Borges would never allow this. Instead, it is a mode of thought that relies on the shared circulation of images, metaphors and values. Working on the social imaginary entails both creating and recreating knowledge in accordance with the energies and concerns of all collaborators. The Creative University is built on this mode and it too thrives, because it has realised just how powerful – and in need of protection – these commodities are in a world that is flooded with raw data. It does not teach or research the social imaginary: it creates it, every day, by clever marshalling of the resources it has (including raw data). This is done through its teaching, its research, and its central support structures.

This university exists and does not exist. University of Galway’s ‘Designing Futures’ programme is already helping undergraduates in our joint honours Arts and Science programmes take multi-perspectival pathways through their learning and benefit directly from interaction with professionals across a variety of sectors. They are actively shaping their own futures in ways the traditional Arts and Science degrees did not foresee and those programmes are unlikely to stay the same as a result. Yet we need to go much further if universities are truly to reignite the social imaginary. Like in the short story, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ (1941), a labyrinth of alternatives is in sight at all points in time, and as a multi-dimensional function of time – all those different selves we could be, could have been, and could still be – and yet we turn away from it because it asks us to think in ways in which we are not routinely schooled. That story ends in cold-blooded murder and eternal contrition. In our fear, when faced with multiple simultaneities, multiple versions of ourselves, we choose not to keep options open. Ironically this means we close down our possibilities precisely when we most need to find alternative courses of action.

Let’s wedge the door open then, and keep going in Borges’s labyrinth. No course can run in the Creative University, no research project be undertaken without having first to tell the story, through the words, images, or data most appropriate to it, of how it changes the world. This is both preposterous and perfectly practicable. The short story, ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’ (1941), coolly works through how someone writing in twentieth-century France might re-write parts of Don Quixote word for word, finally alighting on exactly the same words as the original seventeenth-century Castilian Spanish but through their own artistic free will. Such an outcome, Borges explains, results in a piece of art with a radically different meaning from the only seemingly identical original. Context is all.

Accordingly, a university that really believes in the value of creativity will swap out, for example, curriculum review boards composed solely of academics who have designed their modules largely in one time and place and re-establish them instead with cross-sectoral reading / listening / writing communities, whose task is to reflect back to the university just where the plot twists lie: what unexpected new applications might open up from this learning? Which new groups might contribute next time and how will they change the curriculum? Even if this board created exactly the same programmes, those programmes would sit in a radically different place in society. Inspired by Borges, Mulgan and I might continue to re-set foundational points of practice. Research ethics approval will expand from the current singular focus on risk, to a multi-vocal exercise in uncovering opportunity. How will this piece of research make society a better place, as imagined and endorsed by all its end users?

Am I lost in a social imaginary that is all words and no action? I don’t think so. If the big-picture of all choices and why they matter is properly to come into focus and provide a sharp and compelling framework for how society organises and funds knowledge creation, I might have to temper some of Mulgan’s idealism about teaching radically interdisciplinary courses. He might have to help me navigate what is palatable to politicians and those who elect them. We would need other people in the room to both open up and close down different ideas of how to work with the hopes and fears driving conversations in our communities and across multiple industries. But we would do so from a crossroads at the edge, a connective space that is not falling, but instead stretches out, open-ended, into multiple futures. A university’s job is to communicate in dynamic, creative ways the knowledge that will allow us to find our way into those futures – and, if necessary, back again.

Profiles