Equality laws in Ireland prohibit discrimination under nine characteristics: gender, civil status, family status, sexual orientation, disability, religion, age, race, and membership of the Traveller community.

Language does not feature in this list of characteristics, but should it?

We know from many research studies that discrimination can often occur because of people’s linguistic background. Whether it is in employment or housing or in many other categories of daily life, linguistic aspects such as accent, competence and difference can lead to conscious or unconscious exclusion processes. As has been observed by scholars, language can in effect be the gateway or proxy for other forms of discrimination where social or racial factors are inferred through language.[1]

In bilingual countries, language issues can often be considered in terms of equality, justice and human rights: witness, for example the recent discussions relating to the decision by the European Court of Justice in March 2021 that information on veterinary medicinal products sold in Ireland should be in both Irish and English.

However, while debates about the use of the Irish and English languages are often framed in terms of human rights, for other languages in Ireland, these are considered more in terms of integration and language learning.

Protection for languages other than Irish and English is markedly absent from Irish legislation: the Official Languages Act recognises Irish and English as the two official languages of Ireland but does not provide for individuals whose first language is not one of the two official languages. In Irish Equality legislation, there is no explicit reference to different linguistic backgrounds, language disadvantages, or linguistic barriers preventing access to services or opportunities.

Therefore, although at an EU level, linguistic diversity is enshrined in Article 22 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, in reality, because member states can determine on the ground how to manage this diversity, the situation in Ireland leaves little protection for language rights in multiple languages.

The absence of discussions on linguistic diversity and discrimination is all the more striking given the dramatic changes in the linguistic landscape of Ireland over the last 20 years.

It is a reflection of the increased presence of foreign languages in Ireland that questions on languages now form part of the Census. The 2011 Census was the first to ask questions about foreign languages spoken in Irish homes and it confirmed that Polish was the most common foreign language in Ireland, followed by French, Lithuanian, German, Spanish and Russian.

The 2016 Census showed that 612,018 Irish residents spoke a foreign language at home (up 19% from 514,068 in 2011). This data makes it clear that Ireland is becoming increasingly multilingual with 13% of the population speaking a foreign language at home.

It is worth noting that 30% of those who in 2016 spoke a foreign language at home were born in Ireland. Being a foreign language speaker means less and less being born outside of Ireland: for example, while the number of Polish speakers did not rise significantly between 2011 and 2016, the number of Polish speakers who were born in Ireland almost trebled in this period.

The quantification and analysis of Ireland’s multilingualism is not without its issues: the Central Statistics Office (CSO) lists only 67 languages in their analysis of the Census data and 35,342 speakers from 2016 are listed under the category of “other”.

Grouping so many people and languages into categories such as “other African languages” and “other Asian languages” makes it difficult to understand the diversity of languages in Ireland and illustrates how Ireland is still in the early stages of analysing its linguistic map, let alone embracing it.

Furthermore, even though a question on proficiency in English for non-native speakers of the language was allegedly introduced to the Census in 2011 to enable the state to target resources in areas such as education and health, the reality is that both sectors have experienced great deficits in accommodating linguistic diversity, despite the growing evidence of the need for investment in this area.

Apart from the sheer numbers constituting a multilingual Ireland, there are other reasons why we should be paying attention to linguistic diversity in 2021.

The current pandemic has made it clear that unless health information is made available to linguistically diverse groups, exclusion will be perpetuated. As we address global challenges, we cannot face them in a monolingual manner.

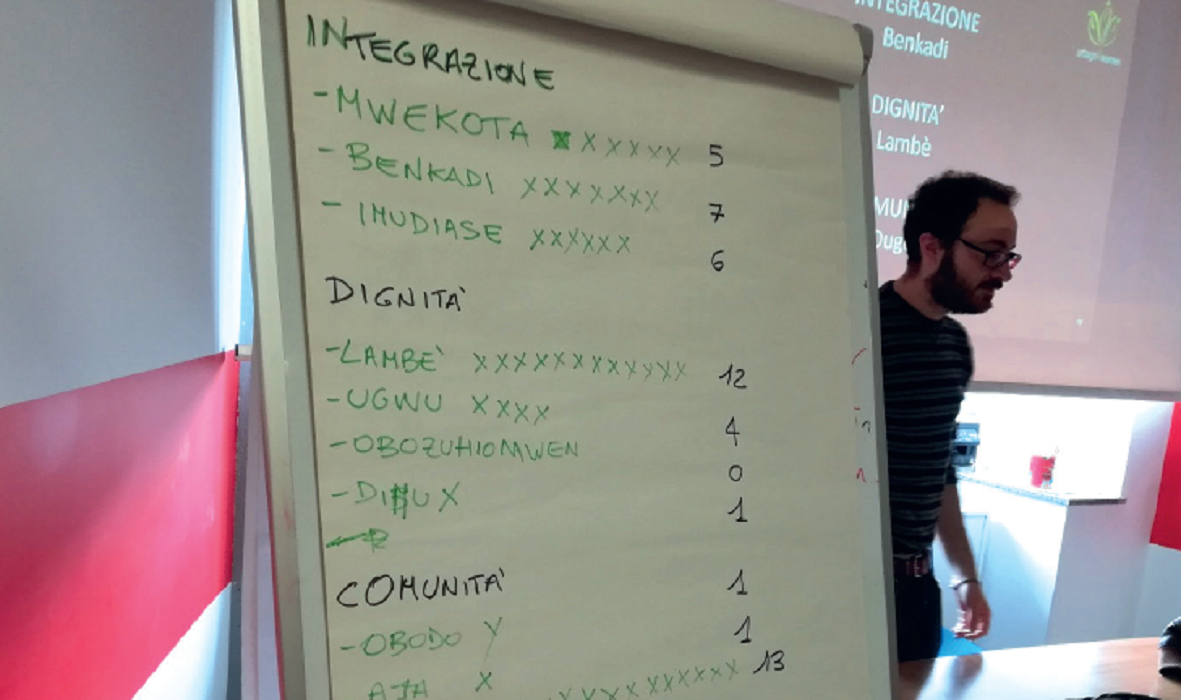

Social forces and movements have revealed that in debates on institutional racism, language needs to be part of discussions on equality, diversity and inclusion. The understanding of languages as part of an inclusive Ireland and an inclusive world is underscored in projects undertaken in NUI Galway in the last four years including My Story/My Words and LINCS.

In both projects, collaboration with NGOs (the Immigrant Council of Ireland, the Italian NGO Tamat) was mutually beneficial in terms of knowledge exchange, working towards the common goals of promoting linguistic diversity as a factor of cultural enrichment. In LINCS, a two-year secondment of researcher Dr Andrea Ciribuco at Tamat NGO enabled in-depth research in settings like a community garden co-managed by asylum seekers, a dance workshop, or a community food making event which enabled participants to tell their stories in innovative ways.

In order to understand the multiple aspects of linguistic diversity, it is important to go beyond the most obvious settings, like the language classroom, and see how the different languages in an individual’s repertoire influence various sectors of their lives. The diverse words used are assorted tools with which to understand and represent the world, and while linguistic diversity can mean initial incomprehension, working to bridge that incomprehension brings greater richness. Whenever individuals are (more or less openly) made to forget their heritage languages in favour of the dominant one, the loss is incalculable – as Indian/Irish poet Nita Mishra aptly puts it:

I know ‘good migrants’

Assimilated families

Good peaceful people

Who have ‘learnt’

To keep their voices under wraps

Pick up the local accent

Have parties to assimilate

And

Over the years

A slow realisation dawns

Upon them, that

They are still

Different, migrants

Foreigners

And the colour of the skin

Hasn’t paled

Even a wee bit

In vain

Was it all worth?[2]

If heritage languages are undervalued (either by society or by migrants and parents), assimilation can result in the effacement of identity and personal history. That is why initiatives such as the Mother Tongues festival are so important in celebrating linguistic diversity in Ireland.

Through linguistic awareness, the values of respect and intercultural competence can be fostered.

In NUI Galway, the activities of the Emily Anderson Centre for Translation Research and Practice, and the Centre for Applied Linguistics and Multilingualism (CALM) have been working to promote understandings of the importance of multilingualism and to view translation as a way of understanding and negotiating meaning across each other’s social “bubbles”.

Research into diverse forms of linguistic engagement in society, such as cultural expression, food, sport, education etc, illustrates the complexity and the intertwined nature of human interaction through the prism of language. The work underlines the importance of studying social divisions in conjunction with language issues and the acceptance of the deep interconnections between multilingualism, diversity and identity in 21st century Ireland.

References

[1] Baumgarten, N., & Du Bois, I. (2019). Special issue: Linguistic discrimination and cultural diversity in social spaces. Journal of Language and Discrimination, 3(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1558/jld.39977

[2] See O’Connor A, Ciribuco A. and Naughton A, ‘Language and Migration in Ireland’ (2017) p.35. https://www.immigrantcouncil.ie/sites/default/files/files/Language%20and%20Migration%20in%20Ireland.pdf