CC: Your research looks to changes in climate from the past to understand the current crisis. Can you explain what this looks like in practice?

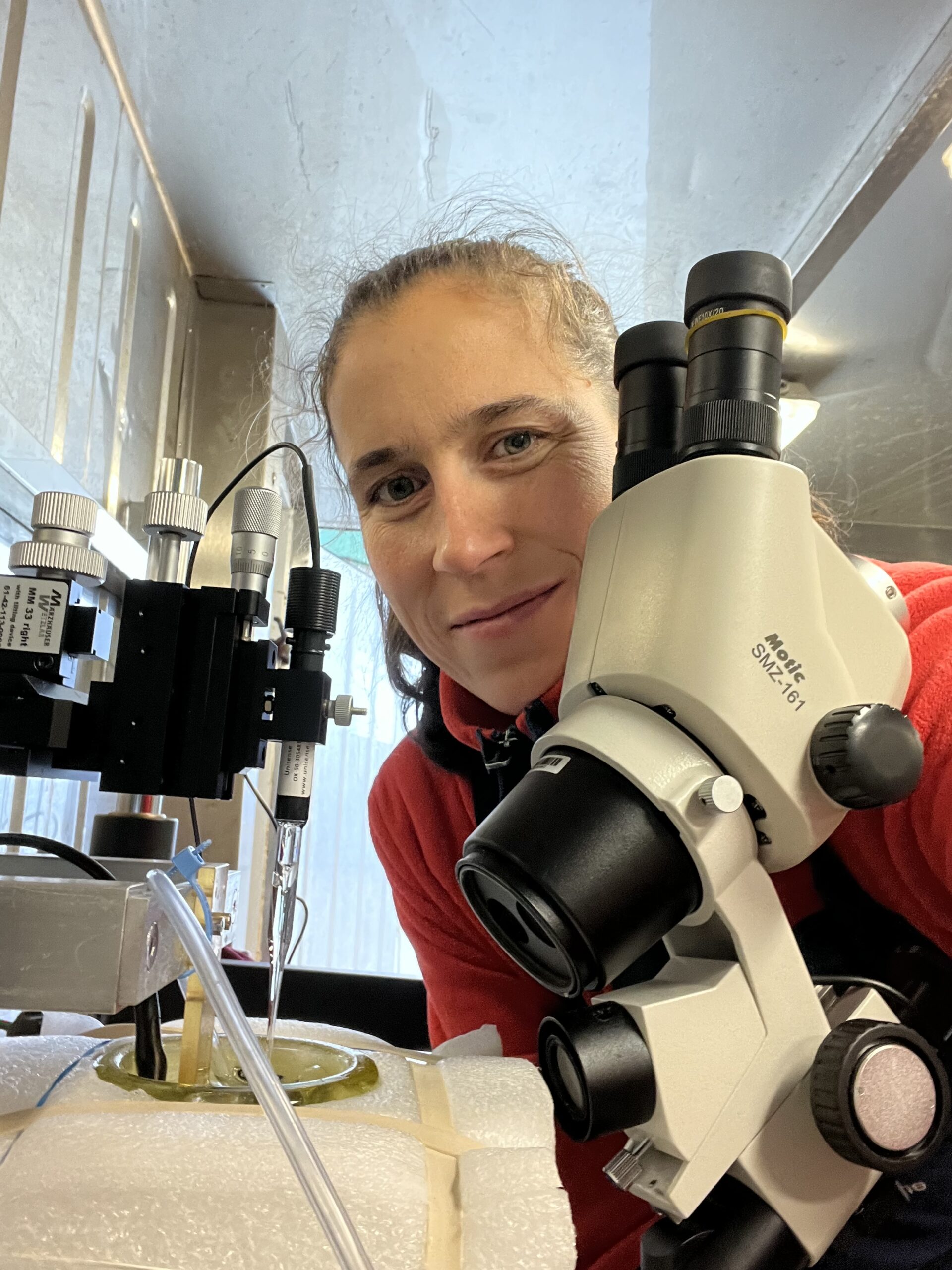

AM: Paleoceanography is the study of the oceans as they were in the past, from a few hundred years to billions of years ago, using this information to understand possible climatic and biotic changes in the future. We measure past climates through indirect measures called proxies archived in marine sediment cores. These proxies can be physical, chemical or biological. As a geoscientist, I focus mainly on small marine organisms called planktonic foraminifera, a ubiquitous group of hard-bodied marine protists. They are unique among marine protists because their calcite shells are well-preserved in marine sediments providing the opportunity to establish the composition of planktonic foraminifera communities in the past.

Like a time-capsule, the geochemical composition of their shells also provides a snapshot of the chemistry and climate of past oceans. This allows us to gain a better understanding of how marine environments have changed over time and crucially, an understanding of long-term climate trends and the impacts of climate change on oceans and ecosystems. My work focuses on two areas. First, I develop geochemical and microstructural climate proxies recorded in foraminifera, to reduce uncertainties associated with past and thereby, future climate predictions. Second, I am passionate about past changes in large-scale ocean-atmosphere climate dynamics during past warm climates to improve our understanding of future climate change.

CC: Expedition CE23011 recently took you on a month-long journey across the Arctic and sub-Arctic Seas. Can you tell us about that experience?

AM: Expedition CE23011 was a 32-day voyage onboard RV Celtic Explorer aimed at studying the Arctic environment and Climate Change to meet the scientific objectives of SiTrAc a GSI-SFI Frontiers for the Future Project. The vessel set off from Killybegs, on the coast of Donegal, Ireland, on the 21st of July and headed northwards to as far as 78° north off the west coast of Svalbard, Norway – continued to work southwards along the east and south coast of Greenland – before steaming due east back home to Galway. The survey was a huge success, and due to phenomenal weather, and a great team of scientists, we exceeded our work program objectives. We felt privileged to be near the ice edge and experience the beautiful scenery, never forgetting the precariousness of the Arctic and its vulnerability to Climate Change. The material collected will now be analysed by a team of international researchers from Ireland, Norway, Germany, and the USA led by the University of Galway.

CC: How did you prepare for the expedition and what challenges did you face?

AM: Preparations for the survey began in early 2023; materials and equipment had to be purchased or borrowed from collaborators abroad to ensure time-sensitive analyses could be performed on board. For example, a Multinet that allows the collection of marine plankton at five different depths was sent from MARUM, the University of Bremen to Galway for the survey. Similarly, the scientific team had to be chosen and prepared for the survey. Regular meetings over six months preceding the survey ensured that we were able to meet the scientific objectives of the SiTrAc work program. Finally, the Marine Institute assisted with preparations every step of the way. They have a phenomenal team supporting seagoing scientists, I couldn’t have done it without them.

Humpback Whale, East Greenland. Image source: RV Celtic Explorer Crew.

CC: Can you explain the significance of your findings?

AM: SitrAc develops an ambitious new approach to assess essential climate variables recorded in modern and fossil planktonic foraminifera using interdisciplinary methods developed in planktonic foraminifera ecology, micropaleontology, biomedical engineering, and geochemistry to significantly advance the field. My goal is for SiTrAc to become a reference point for novel, cross-disciplinary research in palaeoceanography, providing better qualitative and quantitative reconstructions of essential climate variables. This information will enable a major leap forward in our ability to assess the sensitivity of Arctic climate and its role and variability within the global climate system. This will lay the foundation for novel conceptual interpretations, and thereby, an improved understanding of climate change.

CC: These surveys require a lot of time and commitment. Where did your passion for this research originate?

AM: My investment in these expeditions leads to significant advances in paleoceanography because pivotal questions can only be answered at sea. Considering the pressures to publish fast and plentiful, this is a commitment that fewer and fewer scientists are willing to make. Unfortunately, this trend stifles progress and can prohibit the generation of key knowledge on how climate and ecosystems will respond to anthropogenic climate forcing. My passion for understanding how the climate system functions developed from childhood through my education and research at multiple international academic institutions. I love the challenge and the complexity of the climate system and will always strive to advance our understanding of what abrupt climate change will look like. At sea, I love the collegiality among researchers from all over the world. Everyone is literally in the same boat and the focus is on collaboration and never on competition. The excitement of discovery is omnipresent, whether that’s an exciting experiment, a blue whale or icebergs drifting past in the midnight sun. My expeditions also provide a crucial service to the community by training the next generation of ocean-going scientists.

CC: What advice would you give to students entering this field?

AM: Climate research is trans- and interdisciplinary, which means that there is room for every talent and interest. Students and researchers in my research group come from multiple backgrounds including Geography, Ecology, Chemistry, Maths, Geology and Biology. All these combined and more is Palaeoceanography and I find this diversity exciting and enriching. In Geography, at the University of Galway, we are developing a Centre for Paleoenvironmental Research (PRU) which includes five PIs/Lecturers, five Post-Doctoral Researchers, and nine PhD students. Our research is supported by multiple state and international funders. The PRU is a really exciting group and research environment to be part of and I would encourage everyone interested in Paleoclimate research to contact us for current and future opportunities.

SDGs discussed in this article:

Profiles

Audrey Morley is a climate scientist at the University of Galway. She is an Arctic explorer and the President of the Network of Arctic Researchers in Ireland (NARI). In this capacity, she provides objective and independent advice on issues of science in the Arctic to the public and policymakers. Dr Morley’s central research objective is to assess large-scale ocean-atmosphere climate dynamics during past warm climates. The assessments of warm climates are crucial to further our understanding of how Arctic climate change impacts Ireland and how it will change in response to continued global warming.

To support her research agenda at the University of Galway, she has received funding from a wide range of sources including H2020 – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Fellowship, Science Foundation Ireland, Irish Research Council, Geological Survey of Ireland, Marine Institute and Enterprise Ireland. Dr Morley is also an active lecturer and the Director of the BSc Programme in Geography and Geosystems. She provides her students with unique hands-on at-sea training and implements innovative research-led teaching in her classroom.