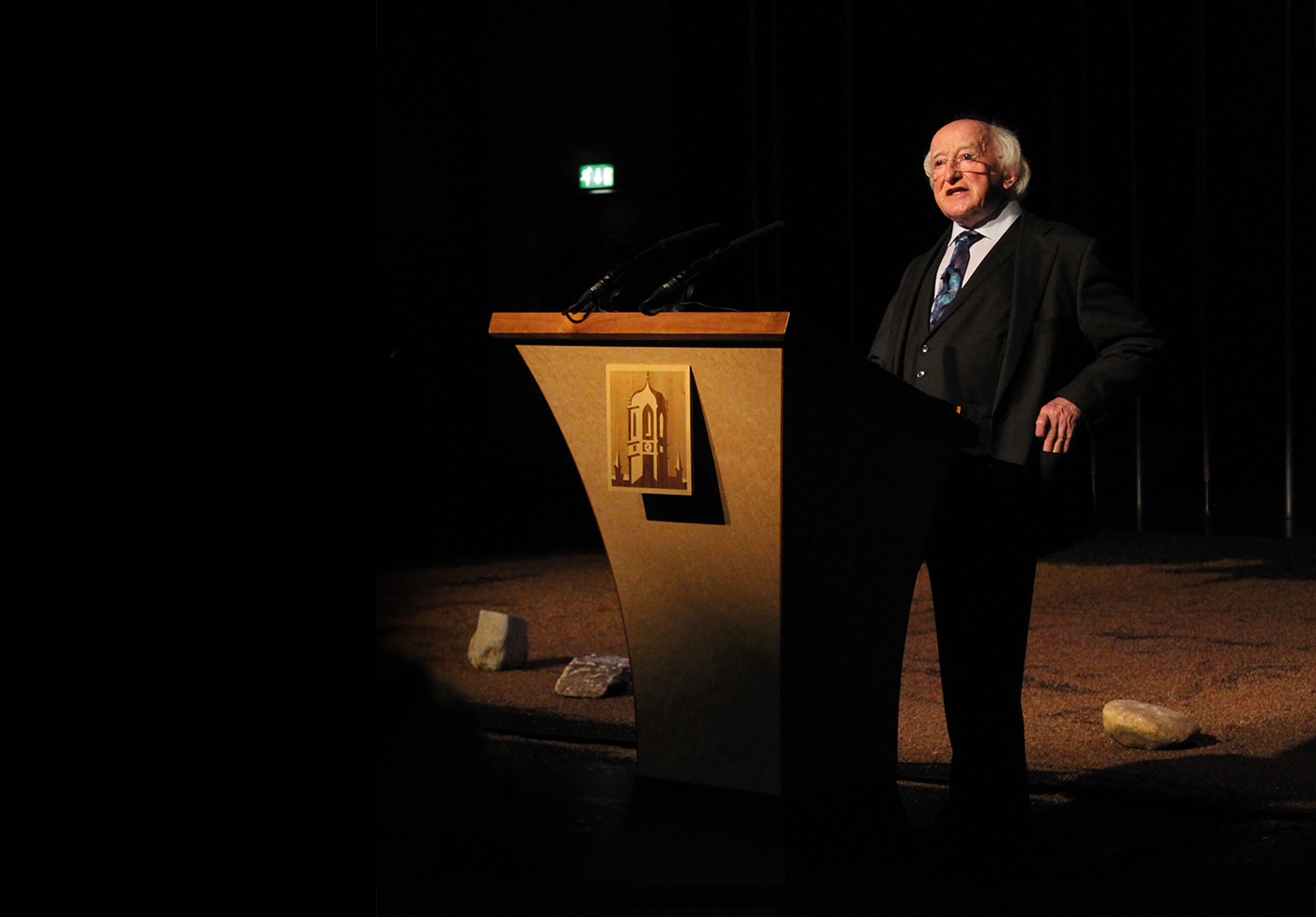

As someone who spent many years teaching political science and sociology in NUI Galway, I feel a close bond with the university, an affection that stays with me to this day as I recall so many wonderful years of teaching and research there, as well as the lifelong friendships forged.

In our present circumstances, as we continue to deal with all the personal, social, economic and cultural consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, we should pause to reflect on the role of academia in our post- COVID world, be it in the intellectual, cultural, scientific, political, economic or social life of the nation.

I am on record as stating, more than once, that I believe the role of academics, and particularly those involved in the public sphere, is to seize moments, to have the courage to provide suitable reaction, to be subversive of received thought, assumptions and fallacies1. Indeed, it was the great public intellectual Edward Said who stated that an intellectual’s mission in life is to advance human freedom and knowledge. This mission often entails standing outside of society and its institutions and actively disturbing the status quo – perhaps even being necessary to assume the role of agitator.

Universities have transformed lives throughout the ages, have been agents of emancipation for so many, and the best examples continue to do so through a broad, balanced and enquiring education, as well as through the wider impact of the research that their staff and graduate students produce. Universities help students to develop their skills and knowledge so that, at their best, they can offer solutions to our great, contemporary interacting crises – ecological, economic, social and, may I suggest, ethical. We now turn to universities in near desperation to provide a basis to assist us in achieving a broader comprehension of the interconnectedness of our social ecological system.

University research, it is claimed correctly, is potentially of benefit to everyone, with the capacity to enrich society and stimulate culture, while of course creating enterprise and economic opportunities, yet it is now facing one of its greatest challenges.

A moment of truth has arrived for third level institutions, that of facilitating an exit from a paradigm that has failed humanity and of offering possible alternatives, new paradigms that will lead to integrated, sustained eco-social policies of sufficiency and equity. What we teach, after all, is the foundation of policy. Good and critical scholarship must include the subverting of what is taken for granted, accepted without question or objection. Exposing the authoritarian and the socially dangerous has been the achievement of universities at their best in times of change. Commitment to such a version of teaching and research must be the core values of a university.

We need to acknowledge that the pandemic crisis that has enveloped the world during 2020 is interlinked with other crises, including climate change – an existential crisis which itself interacts, and is currently interacting, with a range of other crises, including those of an economic, social, democratic and indeed cultural nature. This conjunction of crises is the outcome of historical processes and assumptions. This loss of symmetry was not accidental.

COVID-19 has magnified the shortcomings of our disconnected paradigm of economy with all its imbalances, inequities and injustices, and it has amplified a renewed and welcome demand from the citizens of the globe for a new economic order. This is evident through the response to COVID-19, the burden of which fell to the State, and proved that the State has the ability to play a leading, transformative role in crisis management and is our best shared resource in terms of response, acting decisively when the will is there, offering a paradigm choice we so desperately need. The public sector in its response has demonstrated that it has the capacity and expertise to deliver quality universal services to its citizens, and do so effectively and fairly.

I now ask again, as I have before at international gatherings on the future of higher education2, will universities be allowed to play their part in a new order? Will they seek the space, the capacity, the community of scholarship required to challenge such paradigms of the connection between economy, ecology, society, ethics, democratic discourse and authoritarian imposition as have demonstrably failed? Will they, drawing on their rich university tradition, seek to recover moments of contention and discourse, seek to offer alternatives that propose a democratic, liberating and sustainable future?

In a world of increasing polarisation, where the role of evidence, science and research is under threat, fostering the capacity for constructive dissent is a core function of the university. Third level scholarship has always had, and must retain, a crucial role in creating a society in which there is an openness to consideration, and critical exploration, of alternatives to any prevailing hegemony for the betterment of society.

I believe that a university response, which is critically open to change and originality, both in theory and research, committed to humanistic values in teaching, open to heterodoxy, has an opportunity to make a global contribution of substance to the great challenges and crises we face – from climate change and biodiversity loss, to the democratic crisis, human development, global poverty and indeed pandemic mitigation. I believe that such a university can be, and will be, celebrated by future generations as the hub of original, critical thought, and an advocate of its application through new models of interconnection between research, policymaking and society.

If we wish to develop independent thinkers and questioning, engaged citizens, our universities must, while providing excellence in professional training, avoid an emphasis that is solely or exclusively on that which is measurable and is demanded by short-term outcomes. Debates about the role of the university in recent times are taking place in a narrow political and ideological space.

We must confront a prevalent, flawed and dangerous perception that the necessary focus of higher education must be on that which is exclusively utilitarian in a narrow sense, immediately applicable and whose value is seen solely in financial or economic terms. Such a view sees the primary purpose of the university, and those who study within it, as being in preparation for a specific role within the labour market, often at the cost of the development of wider life-enhancing skills including creativity, analytical thinking and the broadening of horizons so as to enlarge our understanding of human experience.

We will come through this pandemic and learn from it. For out of such a crisis, we are presented with perhaps a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do things better, and from different assumptions, reflections and purposes, to embrace and bring to fruition a new paradigm of existence with each other, in relation to work and living, and with the world itself; a renewed and healthier connection of society, sustainable economy and ecology.

What better memory of one’s days at university, shared days of curiosity, life and love might one have?

It is my great wish that universities will play a key, transformative role in helping to bring about such a paradigm shift; that those teaching in universities are permitted, encouraged even, to impart alternatives; that universities seek to deliver their capacity to deliver a creative consciousness and participatory citizenship, for universities are central, perhaps our greatest hope, to the flourishing of a renewed society post-COVID-19, one that is open to new beginnings and alternatives, and which places values of inclusion, sustainability, and equality at its core.

I will conclude with a quotation from the Second Glion Declaration3, Universities and the Innovative Spirit:

1 See, for example, “Humanitarianism and the Public Intellectual in Times of Crisis” – Distinguished Lecture by President Michael D. Higgins, Fordham University, 30th September 2019

2 Speech at the European Universities Association Annual Conference by President Michael D. Higgins, NUI Galway, 7th April 2016

3 The 2nd Glion Declaration: Universities and the Innovative Spirit, 01/06/2009: Gilon Colloquium