We may not associate SDGs with culture, but the UN’s 2030 Agenda acknowledges the need to safeguard the world’s diverse cultural heritages, and the role of culture in fostering a collective sense of responsibility and belonging.

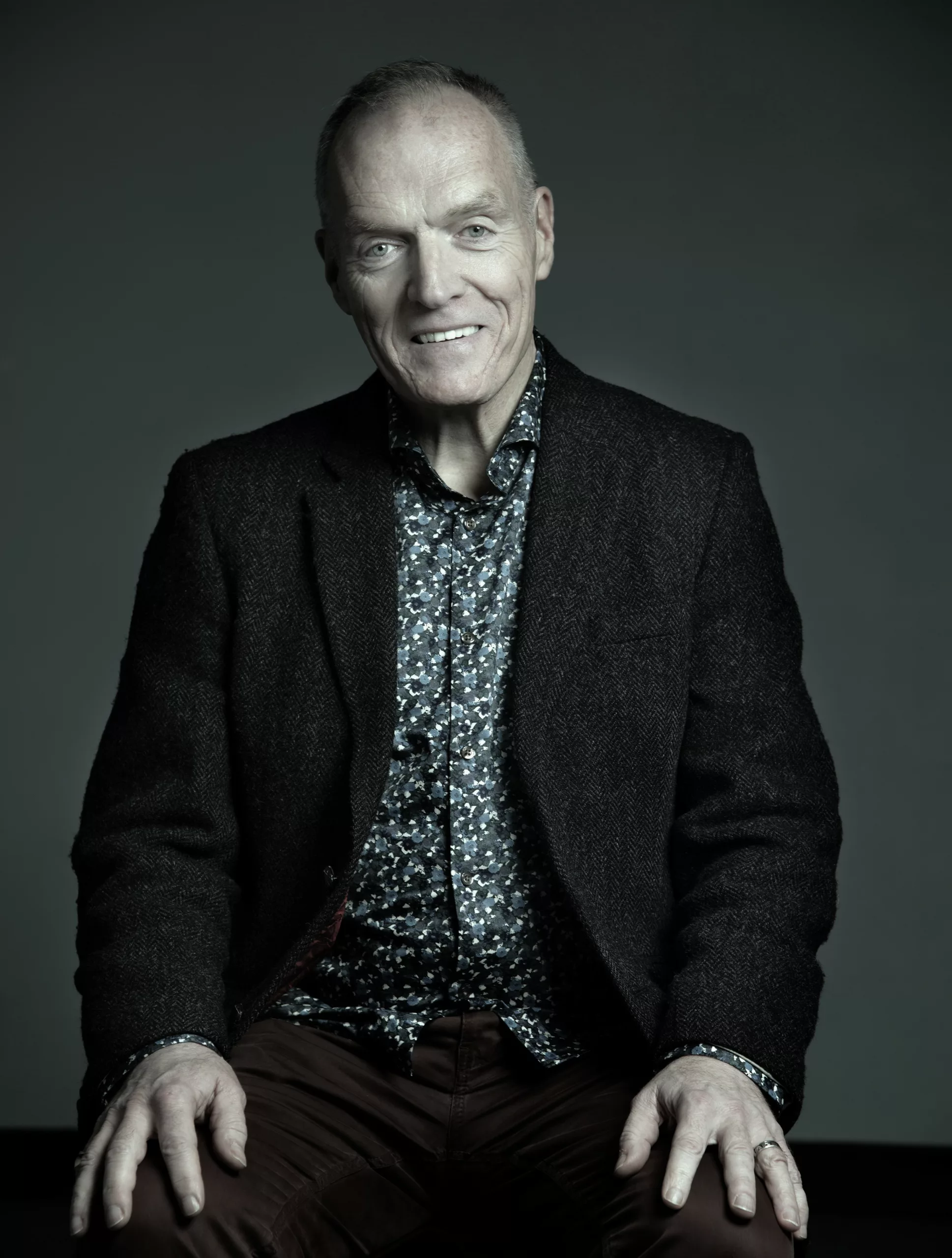

Award-winning writer and singer, Prof Lillis Ó Laoire asks: how can we steward our cultural heritages to realign them with sustainable futures?

The development of viable goals for environmental survival and prosperity are urgent topics for everyone nowadays. In considering environment, people mostly gravitate towards issues of water and air quality and the protection of flora and fauna. To broaden the discussion, it’s relevant to ask what a reflection on cultural sustainability can bring to the debate. As a human-made solution to a human-made problem, sustainability calls for a greater understanding of ourselves – our sense of belonging, cohesion and responsibility as social beings. How can we steward our cultural heritages to protect and realign them with sustainable futures?

In 2020, a nomination for TG4 Gradam Ceoil, Amhránaí na Bliana, did me a great honour. The recognition, for me, delivered a validation of work that I had been doing over the course of a thirty-year career in university education, research and of performance. Questions that came to me at the beginning of my working life resonate now with the concept of sustainability. How could I be a responsible steward of the song tradition of the Irish language? How could this work have more impact? How could I facilitate a thriving indigenous tradition for future generations to reach greater understanding among a wider audience?

Take Tory Island, the most remote inhabited island in Ireland, for example. Tory Island is an area of intense cultural interest located off the north coast of Co. Donegal. Despite being collected and archived by various individuals and agencies, the island’s rich song tradition was in danger of being forgotten by a young generation striving to navigate a rapidly changing cultural and economic environment. Change meant adaptation to a present in which the past was a liability, a barrier to progress. Progress to these young people often meant getting away, succeeding abroad and assimilating to the culture of their adopted city. Despite being nurtured and socialised in an Irish-speaking environment, the hard reality of ‘progress’ meant this heritage had to be jettisoned or abandoned in order to prosper in the real English-speaking world.

My first project, Ar Chreag i Láar na Farraige: amhráin agus amhránaithe i dToraigh, which also appeared as On a Rock in the Middle of the Ocean: Songs and Singers in Tory Island, addressed these issues by describing and explaining the inherent richness of this culture, that had allowed its bearers to live well in a remote and often isolated location for hundreds of years. A strategic intervention aimed at honouring older song custodians and re-awakening interest among the young, it has worked well. The project has given rise to younger generations of singers in Irish, keeping the maintenance of this culture at the forefront of island life. Although not conceived with sustainability in mind, I can see, on reflection, that sustainability as a concept encompasses my objective. We may not associate the SDGs with culture, but the UN’s 2030 Agenda acknowledges the need to safeguard the world’s cultural heritages, and the role that culture plays in promoting social cohesion, diversity, identity and wellbeing. In connecting with these songs, a new generation can understand itself as part of a greater story, extending across generations. Placed in a historical context, my work has intuitively followed a thread of cultural stewardship central to the vision of University of Galway from the start, reaching back well before the Queens Colleges emerged in the second half of the last century.

A pivotal nineteenth century book on Irish song was Irish Minstrelsy (1831), compiled by historian James Hardiman, later Queen’s College Galway’s first librarian (1849-55), out of fear that Irish song was being lost and forgotten. Hardiman’s work as a custodian and guardian reflects much of what the disciplines of History and Irish continue today. One of Hardiman’s followers, Tomás Ó Máille, first Professor of Irish in University College Galway (1909), also showed keen interest in sustaining and developing the local performative heritage of the Irish language. Having studied in Liverpool and Germany, his doctoral work in Old Irish, and his activism for sustaining and developing Modern oral culture likewise blazed a pioneering trail. True to his word, he established a ‘great centre of Irish Learning’ (Ó Madagáin 1999). His use of modern sound recording devices captured the voices of Irish speakers in areas of Connacht and Clare where the language was almost gone. Lying unheard for over ninety years, these recordings remained viable and have now been digitised.

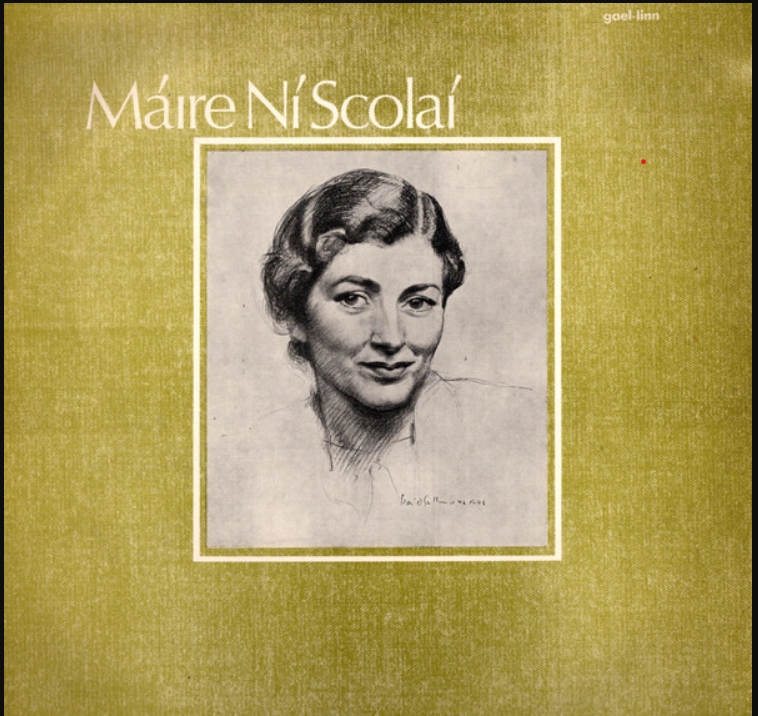

Over 500 audio tracks are gradually being released by the Hardiman Library and can now be heard for the first time since they were recorded here. (1) On the second recording on the site, you can hear the celebrated singer Máire Ní Scolaí (1909-1985), an early luminary of [National Irish Language Theatre of Ireland] An Taibhdhearc with three songs, one in Scottish Gaelic.

Dr Deirdre Ní Chonghaile (Co-PI) has dedicated many hours to aiding this amazing recovery. Deirdre and I developed a travelling exhibition highlighting Prof Ó Máille’s work as an innovator who instinctively understood the importance of sustainability. (2) Recent funding from the President’s Office ensures that the project remains sustainable, supporting public lectures in each venue. Saíocht agus Saoránacht: Tomás Ó Máille has appeared on Campus, in the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin and throughout the West: in Corr na Móna and Mám in Co. Galway, Ceathrú Thaidhg and Westport in Co. Mayo, and most recently in Ennis, Co. Clare, to great acclaim. The exhibition engages local rural communities and scholarly audiences alike. On several occasions, descendants of those recorded have, proudly and poignantly, communicated their association with Ó Máille’s far-seeing cultural stewardship. Such contacts help us to see how important it is for individuals and communities to see that their forebears’ lives mattered, and to recognise their efforts in handing down the rich heritage of Irish to future generations.

Rev. Daniel J. Murphy, a Sligo native, assembled a massive collection of over 1,200 songs and other material in Irish from migrants to the coal mining districts of Pennsylvania from the 1880s to the 1920s. After Murphy’s death in 1935, his manuscripts came to Professor Ó Máille at the University of Galway in 1936. Though Ó Máille himself died just eighteen months after the arrival of this historic archive, his handwritten notes on the pages show that he had begun his research to bring this incredible treasure of pre-Famine memory to the eyes and ears of the public. The goal now is to ensure that Ó Máille’s replenishing vision of cultural ecology will be realised – a vision of sustainable traditional capital that holds enormous potential for renewing community and enhancing transglobal links. In commemorating this heritage, we are bringing the lives of the singers, their hardships and their struggles, vividly to life. Audiences can now appreciate that all was not toil and effort, but that music and story empowered people to rise above the drudgery and danger that characterised their existence.

The talented and enigmatic sean-nós singer, Joe Heaney was the subject of another collaborative international project that I had the privilege of leading. Assembled by the University of Washington after Heaney’s death in 1984, a copy of the archive later came to the University of Galway. Together with the publication of an award-winning biography of Joe’s life, co-written with Professor Sean Williams of Evergreen State College, Washington, the archive was digitised with support from the Irish Research Council. Maintained by Michéal Mac Lochlainn of Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge, the archive is now a dynamic site comprising of over 300 items, mostly songs and Heaney’s narratives about them. The local community in Carna engages in the maintenance and promotion of the archive as part of the area’s renowned song tradition.

The biography Bright Star of the West: Joe Heaney, Irish Song Man (2011) and the archive also provided invaluable assistance for Pat Colllins’ multi-award-winning feature film Song of Granite (2016). Here, you can listen to and see Joe Heaney sing ‘Caoineadh na dTrí Muire’ or ‘Caoineadh na Páise,’ a stirring religious song about the crucifixion of Christ, learned in his own community. The video clip from the site shows Joe Heaney singing for Frederic Lieberman, an American ethnomusicologist, and two others in New York. The diasporic connection is important in that it reveals the links to Rev. Murphy’s collection and to Ó Máille’s wide-reaching vision for the sustainability of Irish oral performing arts.

Such initiatives resonate clearly with Hardiman’s goals for fostering Irish song – preservation from loss, close study and wide dissemination. In parallel with these initiatives, cross-disciplinary partnerships with project leader Marie Mahon in Geography, and Political Scientist Brian McGrath, have extended my enquiry into the sustainability of a wider range of rural arts and cultural initiatives. (3)

Although investment in these initiatives has been modest, we have already seen remarkable results from modest means. The maintenance of professional cultural workers with the necessary acumen and skill to realise the goals of sustainable development is crucial. Technological innovation alone will not solve the climate crisis, and many of the skills and lessons necessary for progress can be found in Ireland’s past. They are ripe for repurposing to support a sustainable future. As time capsules of human relationships, identity and hard-earned perspective, songs and stories foster connection and shared knowledge across generations. This cultural enrichment is fundamental to the university’s vision – an essential part of a well-rounded university experience.

Learn more about the university’s Tomás Ó Máille collection here. You can hear present-day singers performing material from the archives here, and learn more about the archives in this video from the Heritage Council.