In working with adult learners in the MSc program in AgInnovation, I often find myself returning to the phrase, ‘It takes a village to raise an innovation.’ This quote is a paraphrase of an African proverb, ‘It takes a village to raise a child,’ and it became popular in 1996 when then First Lady Hillary Clinton published a children’s book with the proverb as its title. (1)

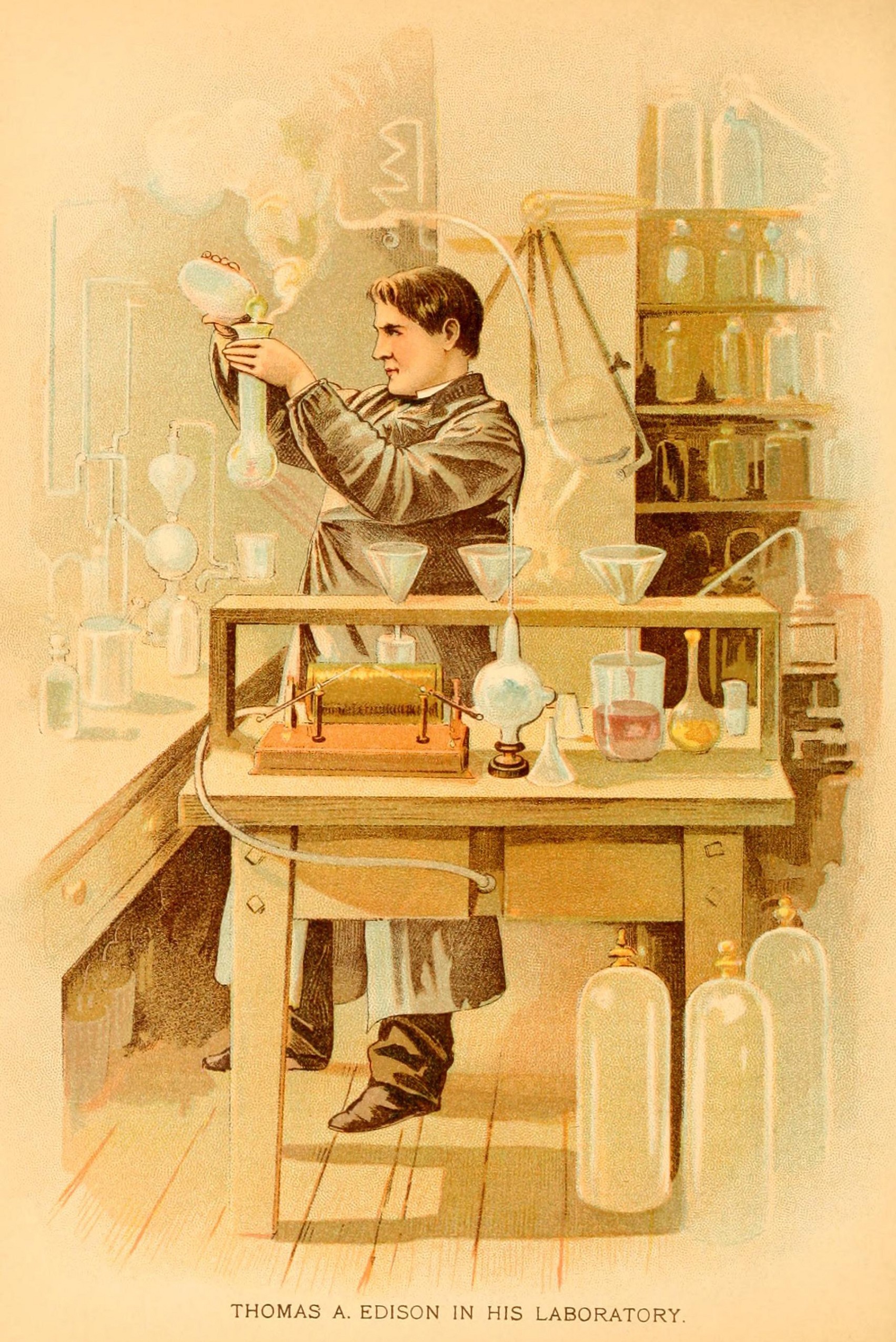

For me, the phrase is important as a means of challenging the stereotypes that my students often associate with invention and innovation. Like so many people, students assume that new technologies are created by individuals working alone. Through some inscrutable mix of genius and luck, creators like Thomas Edison or Steve Jobs come up with amazing new products that revolutionise daily life. Think of the typical image of Edison mid-discovery—a solitary figure raising his test-tube up to the light. He sees all the possibilities, all the meanings, to come from that invention—but what precedes this Eureka moment, and who is involved along the way?

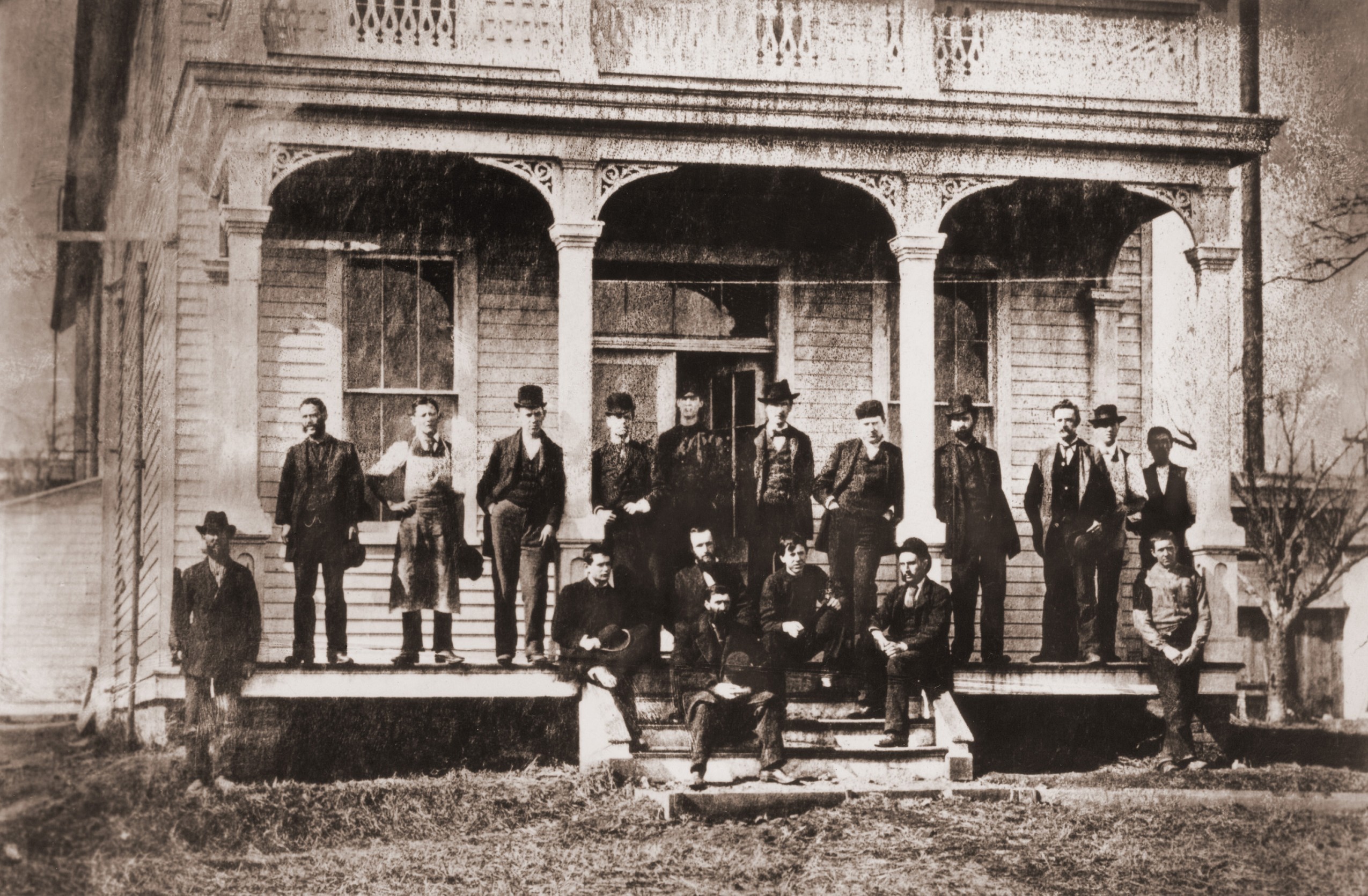

It takes a village to raise an innovation in at least two ways. First and foremost, innovators never work alone. They almost always have business partners, assistants, lawyers and loved ones who provide essential advice, resources and encouragement. One of my favourite inventors, Nikola Tesla, developed his remarkable alternating current (AC) motor in 1887 with financial support from two investors, savvy advice from his patent lawyer, and emotional support from his close male friend, Anthony Szigeti. Equally, contrast the heroic image of Edison holding up the test-tube with the 1877 photograph of Edison on the porch of his Menlo Park laboratory; Edison is sitting there, surrounded by his team of technicians and scientists, looking like just another one of the guys. The lesson here for my students is that, if they want to get an idea off the ground, they need to find people who can provide resources and expertise that complement their own skills and talent. I encourage students at an early stage in their projects, to seek out individuals who can help them perfect their idea.

The individuals in question are not only experts; my students also learn that innovation requires learning from all sorts of people who might buy or use your product. To innovate, students need to go out, listen to people, and learn about their problems, needs and desires. For instance, when the co-founder of General Motors, William C. Durant, was trying to decide whether to enter the automobile field in 1904, he insisted on driving [car manufacturer] David Buick’s prototype car all over rural Michigan. Whenever he could, Durant would stop, show the car to farmers and villagers, and listen to their thoughts and views about automobiles. Drawing on what he learned, Durant refined the design of the first Buicks; indeed, from 1904 to 1908, Durant sold just as many cars as Henry Ford. (2) Innovation is not about imposing a solution on customers, but rather, understanding existing needs and desires. One must wander around the village to discover how to connect new technology with potential markets.

Hence, a hallmark of the AgInnovation program is that we encourage our students to get out of the classroom and learn from people, to discover their most pressing problems or profound wishes. Over the last few years, our students have investigated topics ranging across agriculture, food processing and retailing, rural life, climate change and even beekeeping. In doing so, students interviewed dozens of people, conducted surveys and observed farming operations. To get a full 360-degree view of a problem, our students talk with farmers and their families, as well as consumers and experts in both industry and government. In the entrepreneurial world, this work is commonly known as ‘customer discovery,’ and the goal is to find an opportunity where a new product or service can make a real difference and improve everyday life.

Through ‘customer discovery,’ our students strive to discover, not only what a customer or end-user needs—the functionality of a product—but also the other attributes that will bring delight and satisfaction. To return to Durant’s story for a moment, Durant quickly recognised that his first customers wanted a reliable car and more. They wanted a car that had more power, speed and style. The first Buicks, in other words, had to be real automobiles—not simply ‘horseless carriages.’ Similarly, several years ago, we had a nurse on the AgInnovation programme who investigated whether Irish heather honey could be used to create a new bandage. In her research, she confirmed not only that honey is effective at preventing bacterial infections but through interviews with fellow nurses, patients and their families, that there was a significant interest out there in a wound dressing that relied on a natural product. In both these examples, we see that an innovator’s most creative work is often done in the shaping of values, feelings, ideas—the meanings—that come to be associated with a new product.

As interesting as pyroceram was, Stookey had no idea what to do with it. One day, however, he mentioned the thermal properties of pyroceram to Corning’s then vice-president for marketing, R. Lee Waterman. Waterman asked Stookey if the pyroceram could be made white. Stookey said, ‘Yes, but why white?’ to which Waterman replied simply, ‘Wedding gifts.’ Based on his marketing expertise, Waterman realised that pyroceram could be made into kitchen casseroles—a perfect gift for newlyweds. As an innovator, Waterman was shaping the potential meanings around Stookey’s remarkable new material. Introduced to consumers in 1958, CorningWare was one of the company’s most successful products. Dispelling the myth of the solitary innovator, these stories stress the significance of collaboration for any aspiring innovator or university curricula. In the humble CorningWare casserole, we can see how it takes a village to raise an innovation that is both useful and delightful.

(1) Clinton, Hillary Rodham. (1996). It Takes a Village: And Other Lessons Children Teach Us. Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

(2) Dunham, Terry B.; Gustin, Lawrence R. (1987). The Buick: A complete History (Third ed.). Kutztown, PA.: Automobile Quarterly.

Profiles

Bernard Carlson manages the AgInnovation and TechInnovation Programmes in College of Science and Engineering at the University of Galway. He recently retired from the University of Virginia where he was the Joseph Lee Vaughan Professor of Humanities in the Department of Engineering and Society. He is the author of Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age (Princeton University Press, 2013) and produced the video series, Great Inventions that Changed the World, for The Teaching Company. Bernie and his wife have relocated to a cottage in Craughwell which they share with their three rescue beagles.

Photo by Tom Cogill.