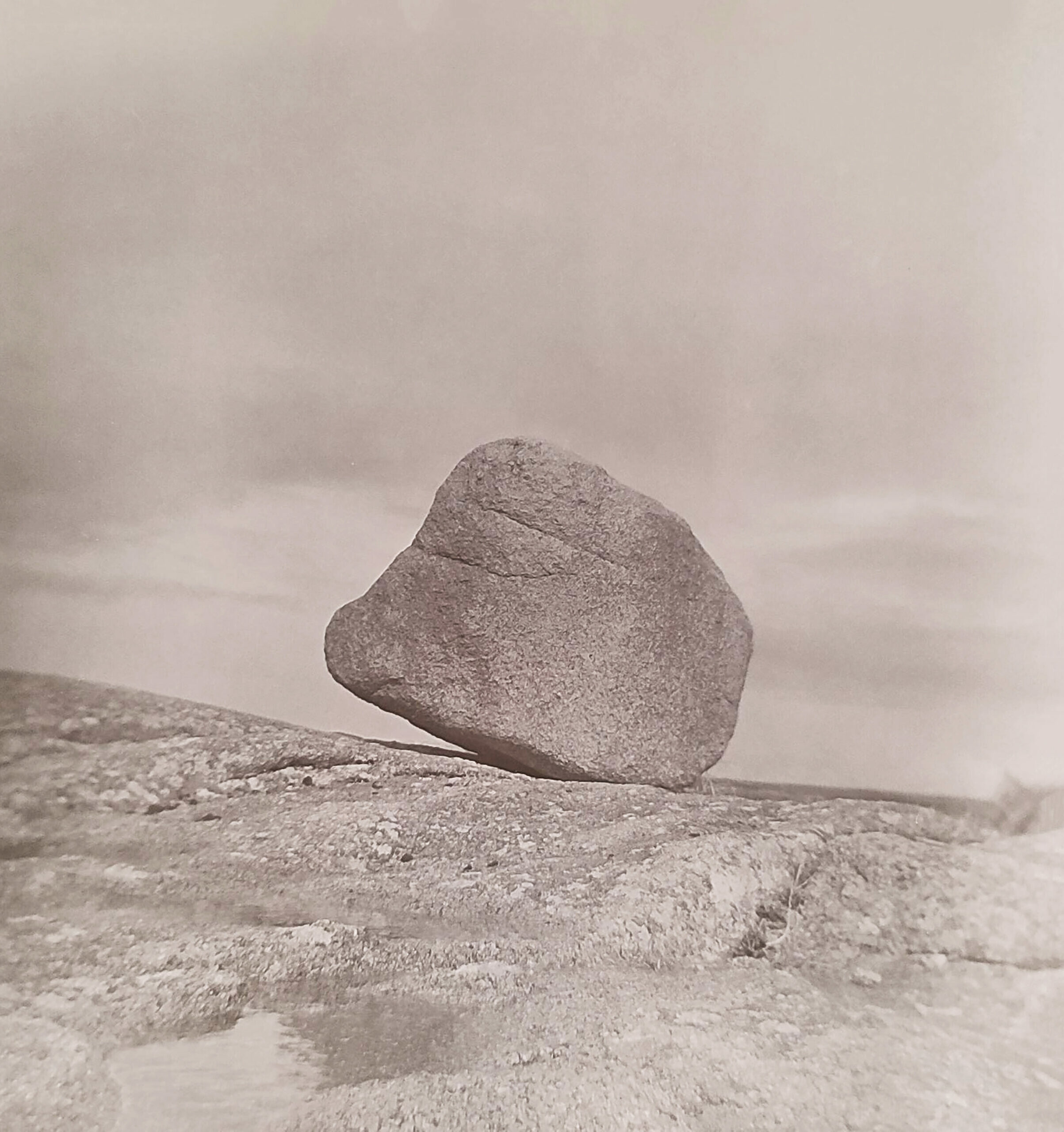

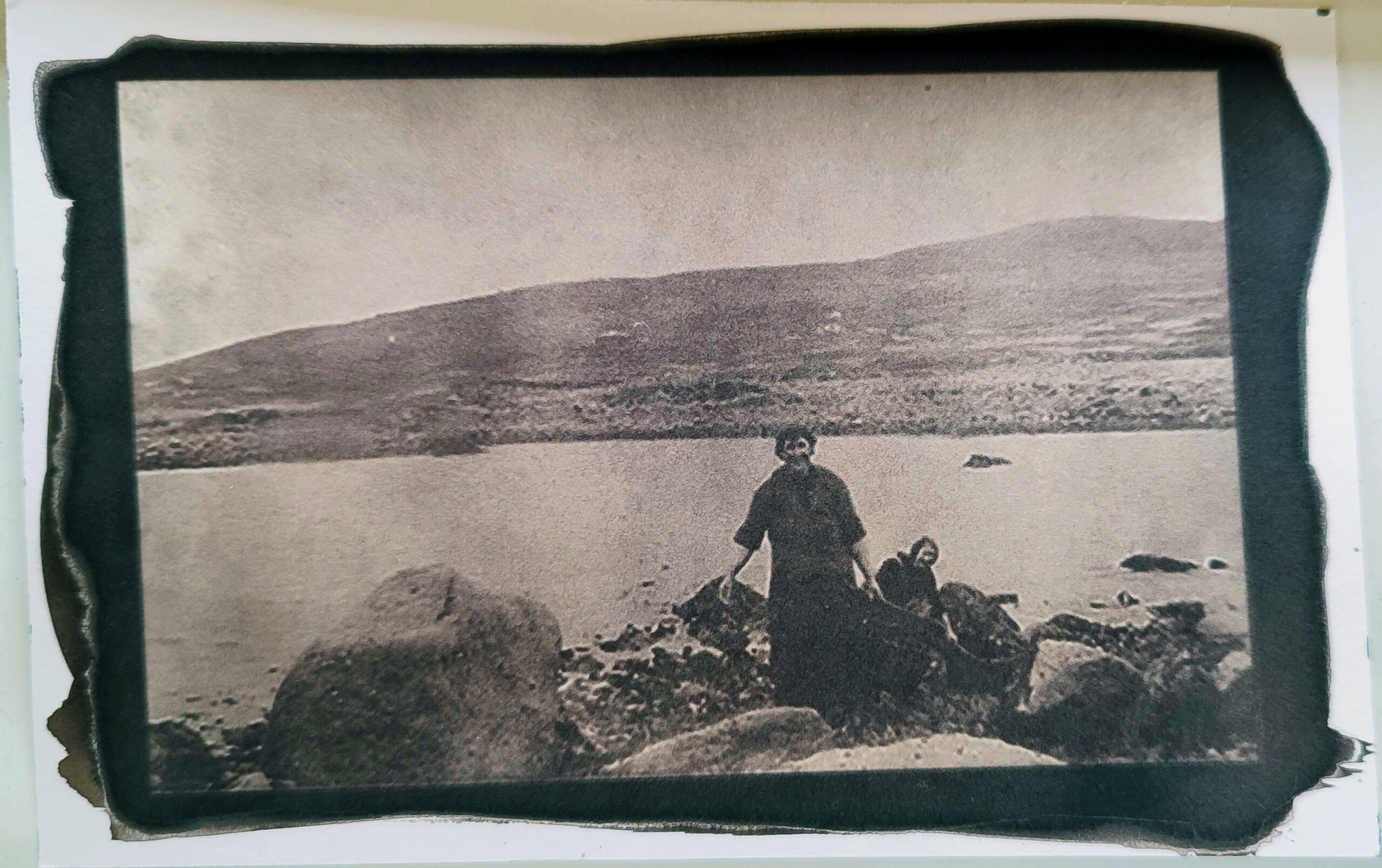

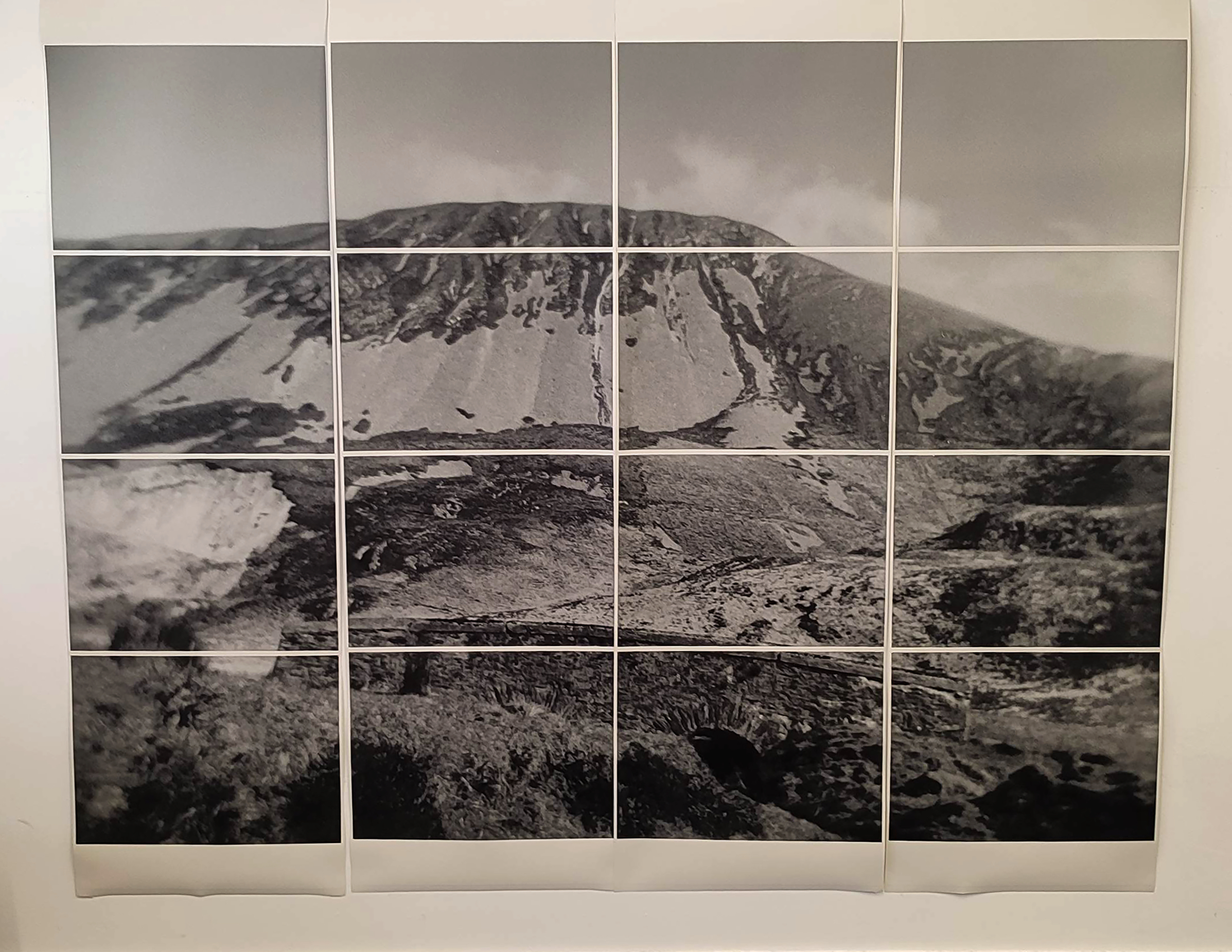

In an essay published in July 2023 in the catalogue for Christina McBride’s Críocha an Chroí / Heartland exhibition in An Gailearaí, Gaoth Dobhair, historians Breandán Mac Suibhne of the University of Galway and Laura Kelly and Niall Whelehan of the University of Stratheclyde respond to her images of the rock-strewn landscape of north-west Donegal.

In July 1752 Richard Pococke, a forty-eight-year-old Englishman soon to become bishop of Ossory, travelled through north-west Ulster when on a more extensive tour of Ireland. Generally stopping with Church of Ireland landowners and clergymen, he rode from the core of the region through its northern and western periphery, that is, from the port-city of Derry through the plantation towns and rolling countryside of the Laggan, looping around the peninsula of Inishowen, before striking across the mountains, bogs and coastal plains of north and west Donegal.

Among those with whom he stopped were the Stewarts of Horn Head (18–19 July), the Wrays of Ards (20 July), and the Olpherts of Ballyconnell (21 July). Further west, there were neither gentlemen nor clergy: he spent the night of 22 July in the “cabin” of an anonymous Gaoth Dobhair “farmer” who wryly informed the English minister—who had insultingly refused to share his host’s food—that he was “the first that ever eat of his own provision in his house.” And from that humble abode he pressed south through Na Rossa, the Rosses.

Pococke was no ordinary traveller. He had spent five years touring the Middle East in the late 1730s and early 1740s, and his three volume A Description of the East and Some Other Countries (1743–45) was a foundational text in the production of European images of the “orient”. A diary he kept as he travelled through Ireland in 1752—not published until the late nineteenth century—is of a lower literary order, being little more than jottings on the “romantic” landscape and things that catch his eye; there is hardly any extended historical or political commentary such as appears in A Description of the East. But details accumulate in those jottings and his diary is a valuable account of life in the north-western corner of Ireland in a period from which there are few. And it is a fine example too of how outsiders have often framed the west of Ireland as strange and “uncivilised”.

For Pococke, the district between Derry and Letterkenny was impressive because it was, to him, like England. The city was “like Guilford”, on a height above a river, and its “handsome parish church”—in fact, St Columb”s is a cathedral—was “something like many churches in large country towns in England”. Likewise, the view over the Swilly as he approached Letterkenny reminded him of the Aire in Yorkshire. It was “a well improved hilly country”; “an exceeding fine country”; it had towns and “large” villages—some of which, like Manorcunningham and Newtowncunningham, had names requiring no glosses—and roads and charter schools, “handsome” houses and land under corn.

But Letterkenny, the gateway between the core and its western periphery, he thought “more beautiful in prospect than when one enters it”. The town had “one street meanly built, with gardens behind the houses and the remains of an old square castle; “the chief trade … consists of shops to furnish the country to the north, and a market for oats and barley, wheat, some yarn and flax.” As he continued north-west, people became poorer: Tully consisted of “a few poor scattered houses”; Kilmacrenan was a “very poor village” and Dunfanaghy “a very poor small town”. And the landscape, if still romantic, became evermore strange. There were mountains and bogs to be crossed and rivers to be forded; he was “extremely surprised” when, from a height, he saw “spots of corn”. The mode of living was different too. Just a few miles west of Letterkenny, he remarked on strange houses built of sods supported by a wooden frame: “the poor people sometime leave with their effects when the hearth money [payment-date] approaches.” The pockets of “civilisation”—marked by clusters of trees and Protestants—around gentlemen’s seats at Cranford, Ards, Horn Head and Ballyconnell only accentuated the “wildness” of their surroundings.

Ultimately, Pococke finds himself going beyond “civilisation”. On leaving the Olpherts of Ballyconnell—a “large eagle” terrified fowl in the yard as he was bidding farewell—he had to hire two men as guides as “there are no more gentlemen to the west nor to the south for near thirty miles, till one comes to Inniskeel”. Later that day, after crossing several bogs “with difficulty”, he sat down by a river to dine, near Bun an Leaca, south of Cnoc Fola:

Some poor came about me and I bless God Almighty that I had [something] to feed them! The Irish Grace was said. Raghnakoude nrahan, agles da jesk ring Dieu erna Koub Mille; diring Dieu rockown re dering ren en ring er argoud, agus er argoron. (1) In English thus, God blessed the five loaves and the two fishes and divided them among the five thousand; may the blessing of the Great King who made this distribution descend on us and on our provision.

Perhaps Pococke’s most striking description of a “native” is of a woman encountered later that day:

I saw a woman carrying one [a curragh] to a Lough and two children following her, she paddled it along at the head, sometimes on one side, sometimes on the other, and when a puff of wind came she held up her gown for a sail. We cried out to her Bra haskin (well-done) and she answered Maugiliore (well enough).

If the Gaoth Dobhair woman lifting her gown is not the sexually promiscuous Egyptian of Orientalist fantasy, Pococke’s diary—its observations, occlusions and imaginings—is now detailing an excursion into the exotic. Travelling along the coast, he reached the Rosses, a place which he, who had seen the Sahara, thought the “most desolate and … uninhabited part in the world”; and that remark reveals how he was framing what lay before him, for he subsequently notes a yearly cattle fair suggesting the place was not all that “desolate”.

But by then, not only has Pococke’s way of looking become similar to that of A Description, so too had his subject. In discussing whiskey in Cloich Cheann Fhaola, he had taken a philological detour, comparing the Irish use of the word “Usquebaugh” [uisce beatha] to Arabs’ use of the word Arrack. In Gaoth Dobhair, he had gone on a similar tangent, comparing the “corhougan” [corr-shúgáin], for making ropes, with an Egyptian hieroglyphic. And now in the Rosses not only is ros [headland] “probably an old word derived from the Arabic Ross, a head or cape of land” but the very rocks of its sodden mountains and bogs are “of the same red granite as that of Egypt, of which the Obelisks are made.”

Derry had put Pococke in mind of Guildford and the Swilly of a river in Yorkshire; surveying the Rosses, he saw the Middle East.

*

Over quarter of a millennium has passed since Richard Pococke passed through north and west Donegal. And in that time many other visitors have seen its landscape as strange. The “crag and heather desolation” of Gaoth Dobhair appalled the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle who visited in 1849. Its people he thought the “wretchedest ‘farmers’ the sun now looks upon”: “Black huts, bewildered ricket fences of crag; crag and heath; unsubduable by this population, damp peat, black heather, grey stones and ragged desolation of men and things.”

Discerning a great many houses dotted between “crag and heath”, visitors also often remarked with wonder that north-west Donegal could support a large population; and they did so of nowhere more than of Gaoth Dobhair, and of there of no place more than the stone-walled fields that stretch south from Cnoc Fola through Bun an Leaca and An Ghlaisigh.

Here, as elsewhere in Ireland, a shift from an oatmeal- to a potato-based diet—a change beginning to take hold around the time of Pococke’s visit—had allowed more people to subsist on less land and land of lesser quality: the country’s population doubled from about 2.5 million around 1750 to 5 million at the century’s end, and it would continue to increase, to about 8.5 million when the blight came in 1845.

Yet in north and west Donegal other factors drove population growth, not least of which, from the late eighteenth century, was seasonal migration to east Donegal, Derry and Tyrone to labour on large farms and to Scotland to work on farms, roads and construction projects. There is the puzzle, then, that in Gaoth Dobhair—and most especially around Cnoc Fola, the area with the lowest valuation of agricultural land per capita in the west of Ireland—the population not only did not fall during the Famine but continued to grow through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. And there is an explanation: people came home every autumn with Scottish pounds.

For sure, some people from north-west Donegal settled in Scotland, integrating into the Irish communities that grew around the mines and factories of the Lowlands. But in Gaoth Dobhair, Cloich Cheann Ghaola and Na Rossa, seasonal migration to the large farms of the Borders proved remarkably enduring, only tapering off in the decades after the Second World War, its end ordained by the mechanisation of agriculture and the opportunities, for men and women, in and around industrial Glasgow, when, in the bleak 1950s, there were few at home.

*

Christina McBride’s parents were part of that mid-twentieth-century outflow to Glasgow. Born in Bun an Inbhir, Neilí an Dálaigh (1934–2017)—in English, Nellie O’Donnell—left for Glasgow in the 1950s, where she found a job with Woolworths and met and married Barney McBride (1923–2010). A native of Dunfanaghy, between Gaoth Dobhair and Letterkenny, Barney had given up the family farm to emigrate to Scotland where, in time, he got good work as a steel erector in Caldwells Steelworks.

Living in the inner-city Gorbals and later in Toryglen, in the south of the city, Neilí and Barney had seven children, six of whom survived to adulthood. Eileen, who they lost at three months, was buried on St Patrick’s Day with a wreath of shamrocks, symbol of a place she had not lived to see.

Ireland was never far away. Each long summer and school break, the young McBrides left the dark tenements of Glasgow to return to Bun an Inbhir, to stay with Neilí’s parents, Sarah Mhór and Andy. And every Sunday until her death in 2017, Neilí used to sit chatting in Irish with Gaobh Dobhair friends who congregated in the back pews of St Brigid’s Chapel in Toryglen.

A child of immigrants, Christina McBride has, like many her of generation, reared in the Gorbals and Toryglen, Govanhill and Coatbridge, been familiar since childhood with the landscape and language of her mother’s homeplace. She is of the place, one of its people; she knows what she sees. She sees Bun an Leaca, An Ghlaisigh and Bun an Inbhir—her heartland, críocha an chroí.

SDGs discussed in this article:

Profiles

Breandán Mac Suibhne is a historian and director of Acadamh at the University of Galway. His publications include The End of Outrage: Post-Famine Adjustment in Rural Ireland (Oxford, 2017) and, as editor, with Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, Ag Cur chun Fónaimh: Údarás na Gaeltachta ó 1980 i Leith (An Spidéal, 2023).

Laura Kelly works on the social history of medicine and gender history in modern Ireland at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. Her most recent books are Irish Medical Education and Student Culture, c. 1850–1950 (Liverpool, 2017) and Contraception and Modern Ireland: A Social History, c.1922–92 (Cambridge, 2023).

Niall Whelehan of University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, has written extensively on modern Ireland and the Irish diaspora. Among his many publications are The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867–1900 (Cambridge, 2012) and Changing Land: Diaspora.